Arch Daily |

- AD Classics: Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project / Minoru Yamasaki

- Al Jazeera Network Studio Building / Veech X Veech

- Twisted House S Vacation Apartments / bergmeisterwolf architekten

- Hongkun Xihongmen Sports Park / Mochen Architects&Engineers

- James Corner Field Operations’ To Lead Much Needed Revitalisation of Hong Kong’s Waterfront

- TOPOTEK 1’s Martin Rein-Cano On Superkilen’s Translation of Cultural Objects

- Murray Music House / Rodrigo Carazo

- Catalan Church Restored Using Ingenious Tensioning System

- Why Instagram Should Be a Part of Every Architect's Design Process

- White Line / Nravil Architects

- Sweco's Kulturkorgen Offers Gothenburg a Basket of Culture

- Ecotox Centre / Brunet Saunier Architecture

| AD Classics: Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project / Minoru Yamasaki Posted: 14 May 2017 09:00 PM PDT  An aerial photo by the US Geological Survey compares the narrow, monolithic blocks of Pruitt-Igoe with the neighboring pre-Modernist buildings of St. Louis. ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Junkyardsparkle (Public Domain) An aerial photo by the US Geological Survey compares the narrow, monolithic blocks of Pruitt-Igoe with the neighboring pre-Modernist buildings of St. Louis. ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Junkyardsparkle (Public Domain) Few buildings in history can claim as infamous a legacy as that of the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project of St. Louis, Missouri. Built during the height of Modernism this nominally innovative collection of residential towers was meant to stand as a triumph of rational architectural design over the ills of poverty and urban blight; instead, two decades of turmoil preceded the final, unceremonious destruction of the entire complex in 1973. The fall of Pruitt-Igoe ultimately came to signify not only the failure of one public housing project, but arguably the death knell of the entire Modernist era of design.  The gleaming towers of Pruitt-Igoe were to have been a "Manhattan on the Mississippi." . ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain) The gleaming towers of Pruitt-Igoe were to have been a "Manhattan on the Mississippi." . ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain) The construction of housing projects like Pruitt-Igoe was a direct response to the evolution of urban populations taking place in the years after World War II. The rapid growth of American cities before 1920 had slowed dramatically, and even reversed in some cities – including St. Louis, Missouri. More alarmingly for urban experts, those residents flowing out of the cities into the suburbs were largely the wealthier classes, depriving businesses of their clientele and the civic governments of their tax revenue. This mass exodus, they believed, left a vacuum which was gradually filled with slums – the dreaded "blight" which could only be cured by being expunged. With the Housing Act of 1949, $1 billion (over $10 billion in 2017) was set aside to provide cities with loans for slum clearance and redevelopment, sparking urban renewal projects across the United States.[1] In 1950, St. Louis was preparing to create 5800 units of affordable housing with the federal funds provided by the Housing Act. City engineer Harold Bartholomew and mayor Joseph Darst, aspiring for utmost efficiency, decided to satisfy almost half of this goal with a single, massive complex. Initially planned in the twilight of the United States' Jim Crow segregation laws, the project was to be divided along racial lines: black residents would live in the Wendell Olliver Pruitt homes, while their white counterparts would occupy the James Igoe apartments. However, as the project was not completed until 1954—after the ruling in the Supreme Court case Brown vs. Board of Education made "separate but equal" segregation illegal in the United States—it was integrated into a single complex, Pruitt-Igoe.[2]  Much of the landscaping and community amenities Minoru Yamasaki originally proposed were never built, contributing to Pruitt-Igoe's eventual downward spiral. ImageVia pruitt-igoe.com Much of the landscaping and community amenities Minoru Yamasaki originally proposed were never built, contributing to Pruitt-Igoe's eventual downward spiral. ImageVia pruitt-igoe.com This single, enormous project began with the clearing of DeSoto-Carr, considered one of the least habitable neighborhoods in St. Louis.[3] In its place was to be built a collection of 33 modular 11-story apartment towers designed by Minoru Yamasaki of Hellmuth, Yamasaki, and Leinweber. Occupying 57 acres of land, the towers provided accommodation for up to 10,000 residents in 2,870 apartment units. While the composition of residential high-rises towering over manicured plazas drew heavy inspiration from Le Corbusier's Ville Radieuse concept, the buildings themselves more closely resemble his later Unité d'Habitation projects: long, narrow slab structures with window galleries running 85 feet along their length. One notable feature designed to improve both functional and cost efficiency were the skip-stop elevators, which only opened onto every third floor. Staircases then provided access to the floors immediately above and below. The combination of the two was intended to replicate community life on the sidewalks in a high-rise setting, where children and adults alike could gather in sheltered safety.[4,5] Even before it was completed, Pruitt-Igoe was not built as intended. Yamasaki had proposed a number of design elements which were never built: low-rise units dispersed among their larger counterparts, playgrounds, ground-floor restrooms, and additional landscaping were all deemed too expensive by the Federal Housing Administration and cut from the project. It was this constant emphasis on economy that dictated features like the skip-stop elevators, and which only hinted at the troubled times ahead.[6]  Courtesy of "The Pruitt Igoe Myth" Courtesy of "The Pruitt Igoe Myth"  Courtesy of "The Pruitt Igoe Myth" Courtesy of "The Pruitt Igoe Myth" Although Pruitt-Igoe was by no means an award-winning project even at the time of its opening, its design was nonetheless lauded by publications like the Architectural Forum, which had named it the Best High Apartment in 1951. (In 1965, this same magazine reexamined Pruitt-Igoe and reversed its stance, declaring the project a failure.) Unfortunately, while federal policy had struck down legal segregation, the attitudes of many Americans—including many of those living in St. Louis—had yet to catch up. The integration of the Pruitt and Igoe apartments resulted in most of the white residents leaving en masse, along with those black residents who could afford single-family dwellings elsewhere. The only tenants left were those who literally could not afford to go anywhere else.[7] Pruitt-Igoe's fall from grace began almost immediately. At its peak occupancy in 1957, 9% of the complex remained vacant; by 1960, this figure climbed to 16%, and it later skyrocketed to 65% by 1970. Whereas the federal government had provided the funds to build Pruitt-Igoe, its maintenance was to be supported directly by the tenants' rent. With the apartments occupied almost exclusively by a dwindling number of low-income residents, a number of whom subsisted on welfare, there was little money to keep up the 33 towers, and they subsequently fell into disrepair. The situation became a vicious cycle: poor maintenance drove out more tenants, bleeding out the already-strained budget and allowing the buildings to become more and more derelict, repelling even more tenants.[8,9]  After two decades of crime and increasing maintenance issues, Pruitt-Igoe was ultimately demolished between 1972 and 1977. ImageVia pruitt-igoe.com After two decades of crime and increasing maintenance issues, Pruitt-Igoe was ultimately demolished between 1972 and 1977. ImageVia pruitt-igoe.com  Courtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain) Courtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain) It was in this atmosphere that Pruitt-Igoe became a hotbed for criminal activity. The galleries and staircases meant to provide safe community spaces instead became the dominion of gangs; residents nicknamed the galleries "gauntlets," treacherous passages in which they were harassed or even assaulted on their way home. The complex's reputation soured so dramatically that some maintenance and delivery workers refused to enter. By 1958, the St. Louis Housing Authority petitioned the federal government for funding to renovate Pruitt-Igoe; although some of Yamasaki's originally-intended amenities were subsequently installed in 1965, the renovation failed to address the deeper social and fiscal issues which had caused Pruitt-Igoe's prompt nosedive into squalor.[10] In 1972, the federal government finally determined that Pruitt-Igoe was beyond rescue. Over the next few years, the 33 towers were demolished by means of dynamite implosions, leaving behind a vast urban wasteland in the fabric of St. Louis which, to this day, has yet to be filled. Only 600 residents had been left when the order came, a far cry from the 10,000 originally expected to fill the complex. The fall of Pruitt-Igoe came to be seen as symbolic: more than the failure of one housing project, and more than the failure of the such projects in general, it was touted as the failure of Modernist architecture itself. Architecture critic Charles Jencks famously declared, "Modern architecture died in St. Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972, at 3.32 pm."[11] In an interview for Architectural Review, Minoru Yamasaki said simply of Pruitt-Igoe: "It's a project I wish I hadn't done."[12]  The televised demolition of Pruitt-Igoe sparked widespread discussion over what precisely caused the project to fail so dramatically. ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain) The televised demolition of Pruitt-Igoe sparked widespread discussion over what precisely caused the project to fail so dramatically. ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain) In the end, it is as unfair to place sole blame for Pruitt-Igoe's failure on its architectural design as it would be to completely exonerate it. It took the combination of unfortunate design choices, deep-seated racism, and poorly-structure housing policy to produce the twenty-year fiasco that was Pruitt-Igoe. A forest has since grown on the land where the 33 towers once stood, disguising the physical rift they left after their destruction in the 1970's. Their legacy is not so easily disguised, however, and whomever one chooses to blame for its eventual downfall, the name Pruitt-Igoe remains synonymous with the failure of an entire design philosophy. References

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Al Jazeera Network Studio Building / Veech X Veech Posted: 14 May 2017 08:00 PM PDT  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow

© Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow From the architect. Following the launch of the broadcast facilities VXV designed for Al Jazeera Media Network in London's landmark 'Shard' building, VXV were commissioned to design new facilities at the network's headquarters in Doha. The new Network Studio building and Arabic Newsroom studio were built to commemorate the network's 20-year anniversary in November 2016. Al Jazeera became one of the industry's most influential multichannel networks worldwide, reaching more than 310 million viewers in over 100 countries.  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow Al Jazeera Network Studio Building VXV's new design was conceived as a landmark structure annexed to Al Jazeera's pre-existing headquarters. The new development contains 1,650m² of studio space and support areas, with 7,450m² of landscaped public space to be realized in 2018. Shaded by a free-standing canopy cantilevering from a 36m lateral structural support, the open-plan design eliminates walls, partitions and columns to provide uninterrupted views through the studios and public areas.  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow Al Jazeera Network Studio Situated at the core of the new building, the 400m² studio features 360º panoramas throughout the studio and exterior walls. The broadcast studio design goes far beyond conventional 'black box' sets, making the vistas seen through the glass facade part of the newsroom's identity. Polarization filter panels balance the natural light, while integrated LED lighting, imaging technologies, immersive graphics and Augmented Reality add high-definition digital content to the broadcasts. The architecture is responsive, reconfiguring into a range of sets with distinct programme identities. VXV created interior features that reflect the curves and asymmetry of the calligraphy used in the network's logo, which subtly reinforce the Al Jazeera brand.  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow Al Jazeera Arabic Newsroom This ground-breaking hybrid space comprises a broadcast studio and production workplace galleries that provide egress to other parts of the site. The 1,100m² studio contains three individual sets adjacent to open-plan areas with space for 100 workstations. The architecture contains 3D immersive graphics and responsive LED surfaces that reconfigure lighting levels and colour tones as new segments are broadcast. Other technologies capture contextual metadata collected during newsgathering and synchronise it with on-screen graphics and video clips integrated into the main 35m video wall installation.  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow These projects provide a compelling new vision for how architecture, studio design, broadcast media and digital technologies can make production and distribution faster, responsive and more efficient.  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow SET OF THE YEAR AWARD  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow  Floor plan Floor plan  © Hufton + Crow © Hufton + Crow This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Twisted House S Vacation Apartments / bergmeisterwolf architekten Posted: 14 May 2017 07:00 PM PDT  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit

© Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit From the architect. Five vacation houses sharing the same basement (garage) are developed autonomously around a common courtyard in the upper levels. In this way, the roofs of each unit have different shapes that blend with the landscape, remodeling and completing it.  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit The challenge is to find new proportions and relations with the existing, becoming part of the context and contributing with the construction of the place.  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit The compound is placed on a hillside and develops following the existing topography, stopping where the perimeter walls find the existing contour lines of the hill: architecture goes along with landscape.  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit The buildings face the street on one side and the courtyard on the other, shaping this element both as an external space as an intimate and protected place immersed in nature.  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit Traditional materials such as wood and stone have been chosen: quarter logs for the facades and natural stone for the basement. A wooden brise-soleil casts ever changing shadows on the interior, acting on the perception of time and space through the seasons.  Ground floor plan Ground floor plan  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit  Second floor plan Second floor plan  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit  Third floor plan Third floor plan Openings on vertical and horizontal planes of the building envelope frame unexpected views of the landscape and provide a dynamic light and shadow play on the five house volumes.  © Gustav Willeit © Gustav Willeit This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Hongkun Xihongmen Sports Park / Mochen Architects&Engineers Posted: 14 May 2017 01:00 PM PDT  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu

© Hao Shu © Hao Shu From the architect. The project is situated in the center area of Xihongmen Town, Daxing District, Beijing with residential communities inhabited by a large variety of residents. The lack of park and sports resources, and given the limited land available for use, how to maximize the role of limited land and solve more social problems, are two challenges at the beginning of the planning.  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu Therefore, the developer wants to improve the local environment and atmosphere by building the "most beautiful" block of the area. The sports park, is a multi-function green leisure space with fitness, entertainment, family and leisure time function, a sport park meant to grow, to improve the land around it and that will benefit the entire city.  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu Concept Innovation 1. Folded land utilization – Maximum of land value "Folding" is to turn limited plane (land) into multi-level spatial system for maximization of land use.  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu "Folded land utilization" is to properly allocate limited land resource, provide adequate outdoor playground and urban landscaping, and realize the maximum of land value. The project's program includes a stadium, a sports supporting room, a central courtyard, a park and a parking lot. The concept of "folding" is used in each functional space, in different ways.  Masterplan Masterplan 2. Integration of architecture, landscape and interior design "Integration, Compatibility and Improvement" are the initial elements of planning based on which a design concept integrating architecture, landscape and interior has been developed.  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu 3. Green Concept "GREEN PARK,GREEN FUTURE!" The "green" of green concept is more than just a color. It also includes green theme (health), green concept (sustainability), green function (sports), and green perception (peaceful mind).  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu The project intends to provide a sports park that integrates health experience into a green environment. Design: By integrating "green" into the entire design system, the integration design concept of architecture, landscape and interior design is used to create an urban green island which is rated as a three-star green building in China.  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu 4. Parametric design In addition to the innovative design concept, parametric design is employed to deal with complexity of the project. Due to the developer's strong attention, BIM has been integrated into the whole process of design – build – M&O.  BIM1 BIM1 Green Design By integrating "green" into the entire design system, Design content includes: Folded land utilization, Nature-oriented outdoor environment, Sponge type site design, Passive energy saving, Experience-oriented indoor environment.  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu  Section Section  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu "A building is like a seed that is planted to grow and bear fruit naturally in sun and rain." The architects and designers intend to design a sports park that integrates health experience into a green environment, "a growing sports park", cherishing land and benefiting city.  © Hao Shu © Hao Shu This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| James Corner Field Operations’ To Lead Much Needed Revitalisation of Hong Kong’s Waterfront Posted: 14 May 2017 09:00 AM PDT .jpg?1493944015) via James Corner Field Operations via James Corner Field Operations With decaying infrastructure and a lack of viable public amenities, Hong Kong's popular yet problematic waterfront is the focus of James Corner Field Operations' latest undertaking, aiming to transform the site into an attractive tourist and local destination. The equivalent of Hollywood's Walk of Fame, Hong Kong's Avenue of Stars and the Tsim Sha Tsui (TST) waterfront are in need of severe revitalisation, with areas requiring demolition if not reinforced within the decade. The landscape architecture firm's vision incorporates new seating, shading and green space to reinvigorate the promenade while offering panoramic views of the city's skyline as it guides visitors towards the harbor. Trellises will provide 800 times more shade than what is currently offered, while seating will increase 325-fold to encourage public engagement and interaction with each other and the space. .jpg?1493943996) via James Corner Field Operations via James Corner Field Operations In addition to the promenade built upon a seawall, the proposal stresses a strengthened waterfront infrastructure for the site as it serves as a wave break to minimize wave damage on the shore and reduce storm effects. The seawall is clad in custom sculpted precast concrete that encourages underwater habitation and is also composed of interlocking panels to offer additional structural strength. The effects of potential typhoons are also countered with interlocking concrete pavers to withstand submerged conditions, while the trellises form windbreaks upon the shore.  via James Corner Field Operations via James Corner Field Operations Renowned for their revitalisation of the Chelsea High Line in New York, James Corner Field Operations are also currently working on a historic canal in Washington D.C. Once complete, the Tsim Sh Tsui waterfront will function as a much needed attractive public space in Hong Kong, while continuing to withstand the detrimental effects of the rising tides of climate change. News via: James Corner Field Operations.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| TOPOTEK 1’s Martin Rein-Cano On Superkilen’s Translation of Cultural Objects Posted: 14 May 2017 07:00 AM PDT Founded in 1996 by Buenos Aires-born Martin Rein-Cano, TOPOTEK 1 has quickly developed a reputation as a multidisciplinary landscape architecture firm, focussing on the re-contextualization of objects and spaces and the interdisciplinary approaches to design, framed within contemporary cultural and societal discourse. The award-winning Berlin-based firm has completed a range of public spaces, from sports complexes and gardens to public squares and international installations. Significant projects include the green rooftop Railway Cover in Munich, Zurich's hybrid Heerenschürli Sports Complex and the German Embassy in Warsaw. The firm has also recently completed the Schöningen Spears Research and Recreation Centre near Hannover, working with contrasting typologies of the open meadow and the dense forest on a historic site.  © Iwaan Baan © Iwaan Baan  © Iwaan Baan © Iwaan Baan Superkilen, however, remains TOPOTEK 1's most acclaimed project to date. A collaboration with BIG and Superflex, the project involved the design of half a mile of urban space within one of Copenhagen's most culturally diverse, yet challenged neighborhoods. Responding to the area's reputation for violence, the urban park is divided into three sectors that are littered with cultural artifacts and objects from around the world, thereby celebrating the ethnic identities of the neighborhood through the re-contextualization of familiar objects. Translating and trans-locating cultural objects were the focal points of Superkilen's success as a unifying public space, as founding partner Martin Rein-Cano explains in an interview with ArchDaily:

© Iwaan Baan © Iwaan Baan  © Torben Eskerod © Torben Eskerod In addition to fostering a sense of familiarity and cultural acceptance within the community, the three collaborating firms also responded to the area's social difficulties through notions of expression, as opposed to those of repression.

Check out the whole interview with Martin Rein-Cano in the video above. A full list of TOPOTEK 1's completed and ongoing work can be found here.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Murray Music House / Rodrigo Carazo Posted: 14 May 2017 06:00 AM PDT  © Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio

© Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio From the architect. LIVING THROUGH THE EXPERIMENTATION  © Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio Murray Music House is designed for a family of 5 inhabitants, mom, dad and three children, who constantly feedback the design process, being this key for the definition of each space and each corner of the house.  © Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio Taking advantage of site characteristics such as topography, trees and orientation, allowed to adapt to the steep slope of the land, designing a two level house with specific characteristic for each environment. The lower level has the quality of being immersed in the ground and within a wooded area that promotes privacy, generates a threshold of silence and the earth and grass provide climatic comfort, creating cool environments during the day and warm at night. The trees cover a good part of the facades, generate shadows, light projections that pass through the branches and paint the panorama with their trunks, roots and leaves making of this space, located in the depth of the ground, the ideal place for the bedrooms.  © Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio  Ground floor plan Ground floor plan  © Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio The upper level, located at the top of the land, has a wide view to the southwest of the central valley, where trees do not cover their facades. These are cleared to allow the entrance of the greater amount of natural light to the social areas, reason why the terraces, the walls and open spaces become canvases In light of the incidence of the sun. The ceilings expand in order to create the transition between internal and external spaces, containing the various activities of the social core and its extension to the exterior.  Section E-E' Section E-E' The geometry of the house plays a fundamental roll for the understanding and coherence of the various programs involved in the project, through the scale, subtraction and addition granted by the multiple forms. The openings allow natural lighting and ventilation through each of the spaces. The kitchen area extends as an integrating element of the dwelling with the social area, which allows the participation of all the inhabitants in the housework, hierarchizing this space through the height, the overhead lighting, and the views to the landscape.  © Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio The natural elements of the site become accomplices of the design, the house Murray Music is lived through the experimentation, which was the concept of the House, which allowed to arouse the emotions through the experience of the spaces and all its designed details planed in conjunction with his future inhabitants, allowing the appropriation and the characterization of each space.  © Roberto D'Ambrosio © Roberto D'Ambrosio This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

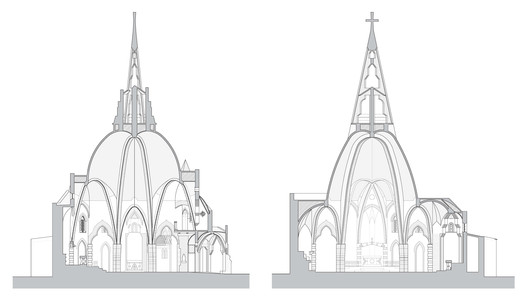

| Catalan Church Restored Using Ingenious Tensioning System Posted: 14 May 2017 05:00 AM PDT  © Santi Prats i Rocavert © Santi Prats i Rocavert The object of this architectural restoration is the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, in Vistabella, the work of Catalan architect Josep Maria Jujol (16 September 1879 – 1 May 1949). The original design dates from 1917 with the construction completed in 1923. The building is a magnificent and personal work of Catalan architecture. Description by the Architect. The use of the building—a temple for Catholic worship—has not changed since its construction, a fact that allows for a clear restorative approach: with the minimum intervention, yet still guaranteeing the survival of the work.  Situation Situation The intent was to treat the problems by seeking solutions in the original design, and to recover the original interior and exterior appearance without erasing any unproblematic changes created by the passage of time—even respecting certain human alterations caused by the historical events that contextualize the building in its time. From this approach, the general criteria for the intervention are deduced for each of the subsystems of the building.  © Santi Prats i Rocavert © Santi Prats i Rocavert As for the bell tower of the church, in 1934 the spire was damaged by the wind and the repair was directed by Jujol himself, incorporating eight steel bars into the inner corners of the tower's four pillars. These straps, extending from the spire's base to the cross, were concreted "in situ" and covered with mortar and bricks along the pillars. Over the years, the concrete protection around the steel came off in several places and the oxidation of the steel bars ended up cracking the masonry.  © Santi Prats i Rocavert © Santi Prats i Rocavert The most conceptually important intervention—though one which is imperceptible in the finished restoration—was the substitution of these passive steel straps for active tensioning straps. This replacement process was monitored with strain gauges and computer control to guarantee the desired tension based on data obtained in scientific and rigorous tests carried out on the bell tower structure itself.  Ground Floor Ground Floor  First Floor First Floor  Roof Floor Roof Floor The additions necessary to optimize and improve the performance of the building in terms of lighting, ventilation, humidity control and temperature are located in the secondary space, the sacristy and warehouse, to serve the main space without any disruption. Once Phase 1, the restoration of the bell tower and the main vault, has been completed, the remaining phases will be carried out with their own constructive logic according to the severity of the problems and the available funds.  Section Section  Section Section  Section Section Architect: Santi Prats i Rocavert This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Why Instagram Should Be a Part of Every Architect's Design Process Posted: 14 May 2017 02:30 AM PDT Instagram is an app. Instagram shows images. Instagram is a verb. Instagram it! Instagram has 600 million users. Numbers are very important. These days, they are an exact expression of what one is, or isn't; by the way, how many followers do you have? Instagram is the great equalizer. I don't think Instagram is about news. Instagram is about influence. It is that very moment when the old order is changed; the moment when the recent graduate changes the established practice. Instagram is space. Have you seen @archiveofaffinities? It is better than any school library. It is the space to spend your most important time. It is a spa. Instagram is superficial. This is a compliment. Its superficiality is beautiful. It is that lightness that comes with judging everything just visually. Instagram is cropping images. Ah! Instagram is synthesis. Instagram is art. Instagram is a timely matter. It is the moment when you realize you are not original. Or even worse, it is the moment when you realize that there is someone better than you. Instagram is high-speed design. Instagram feels like thinking. It is about thinking in images. It is Aby Warburg in square format. A brief primer: Warburg is an iconographer. In his "Mnemosyne Atlas" (1929), various symbolic images, mostly related to a specific Renaissance topic, are juxtaposed and placed in a sequence, in order to construct a visual understanding of the subject matter. It is very important to note that the understanding of the subject matter is immediate. This timely dimension is crucial as it momentarily displaces other forms of rationalization. The brilliance of Warburg was that he was building a counterpoint to the traditional Platonic thinking that considers the image to be the opposite of knowledge. It seems to me that Instagram is about knowledge. Instagram is easy, when you don't care. I recommend my students to have an Instagram account. Instagram requires commitment. There would be a moment when Instagram became part of every single architect's design process. This moment lasts a little over a second. After that second, some of them go rogue. Some of them decide to look only ahead. Instagram is only a temporary abrogation of the polarities of mind. Instagram is openness to the world. For an architect, it is about the public. I love @officialnormanfoster. The architect who has built half of the contemporary world is human. Looking at his amazing doodles or smart-material cycling pants makes me confident. I do not follow it. What I mean is that Instagram is about surrender. How smart is OMA? Nowadays, their website displays primarily images of their buildings as posted by the buildings' "users" via Instagram. How better to showcase your architecture than through the eyes of the public? I am not naïve. It is not perfect and for sure it is curated, but it implies a clear attitude to the relationship between architect and user. Soon, everybody will do it. So, why Instagram should be part of every architect's design process? For me, Instagram is a project. It feels like a construction project. I instagram everyday. This forces me into an absolutely annoying position; that of being bad. I use Instagram only to look back. For me it is the new version of the ultra-clean website. It is the medium through which I open windows into my design process. I try to be honest. The End. PS: Joshua Rothman, writing in The New Yorker, describes Karl Ove Knausgaard's six volumes autobiographical novel "My Struggle":

I started using Instagram around the same time I started reading Knausgaard.  OMA's website shows Instagram photographs by users of their buildings. Image<a href='http://oma.eu'>via OMA</a> OMA's website shows Instagram photographs by users of their buildings. Image<a href='http://oma.eu'>via OMA</a> Adrian Phiffer is founder of the Office of Adrian Phiffer and teaches at the University of Toronto John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design. His Instagram account was included in ArchDaily's "25 Architecture Instagram Feeds to Follow Now (Part IV)." This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| White Line / Nravil Architects Posted: 14 May 2017 02:00 AM PDT  © Mussabekova Ulbossyn © Mussabekova Ulbossyn

© Mussabekova Ulbossyn © Mussabekova Ulbossyn From the architect. We like to make the house as simple as possible and at the same time interesting. The building is located in a landscape of unique beauty. The main goal was to develop the project without harming the natural landscape. The exterior of the house is conceived, that would look different from different sides and due to this you can enjoy the view of a non-repetitive exterior.  © Mussabekova Ulbossyn © Mussabekova Ulbossyn  Floor Plan Floor Plan  © Mussabekova Ulbossyn © Mussabekova Ulbossyn Appearance and interior support the same color, emphasizing the severity and unity of the house. Panoramic energy-saving windows from both sides of the house evoke a feeling of complete openness and privacy with nature. The glass has a reflective property from the outside to reflect trees and clouds, so the house merges as much as possible with the surrounding environment. You can go on the balcony in the morning to drink coffee, enjoy a panoramic view of the horizon and fresh air.  © Mussabekova Ulbossyn © Mussabekova Ulbossyn The interior of the house is simple. Monochromatic white color in the interior allows to maximize the sense of space and not to strain the person, to feel clean and relax comfortably.  © Mussabekova Ulbossyn © Mussabekova Ulbossyn There were minimal excavations at the construction of the house, as the current relief of the site was perfect. The house stands on stilts. The frame of the house is a concrete structure, which is isolated from the outside and then covered with a flexible, smooth white lime plaster.  © Mussabekova Ulbossyn © Mussabekova Ulbossyn This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Sweco's Kulturkorgen Offers Gothenburg a Basket of Culture Posted: 14 May 2017 01:00 AM PDT  The Kulturkorgen offers Gothenburg a basket of culture, inside and out. Image Courtesy of Sweco The Kulturkorgen offers Gothenburg a basket of culture, inside and out. Image Courtesy of Sweco Growing like an outcrop amongst the hills of Gothenburg, the Kulturkorgen by Swedish firm Sweco Architects offers the public an opportunity to watch, engage, and perform. The scheme is a result of an architectural competition for a new Culture House in the city, run in collaboration with Architects Sweden. The winning proposal, who's name translates to 'Basket of Culture', acts as both a building and a square – a social arena where flexible interior spaces act in tandem with a generous public green landscape for recreation and gathering.  A generous public square contains seating, stages, and play areas. Image Courtesy of Sweco A generous public square contains seating, stages, and play areas. Image Courtesy of Sweco  The facade is a rich blend of timber, colour and pattern. Image Courtesy of Sweco The facade is a rich blend of timber, colour and pattern. Image Courtesy of Sweco Folding out from the Bergsjön landscape in Gothenburg, the open, inviting façade of the Kulturkorgen embodies Sweco's vision of a welcoming environment – a rich blend of timber, color and pattern evoking warmth, purity, and curiosity. The landscaped square is rich in amenities, with green areas, seating, recreational spaces, and stages, with the architects emphasizing the importance of an open arena to host a multitude of activities.  Interior functions are organised around a central atrium. Image Courtesy of Sweco Interior functions are organised around a central atrium. Image Courtesy of Sweco  The interior includes informal, flexible space for meeting and talking. Image Courtesy of Sweco The interior includes informal, flexible space for meeting and talking. Image Courtesy of Sweco Inside, the building is organized around a central atrium reaching skywards - a gesture dominating the aesthetic inside and out. The Kulturkorgen contains a library, café, exhibition space, meeting rooms, studio, small theater, greenhouse, as well as adaptable, less programmed spaces for informal talks, meetings, and social events. Together with its public square, the building represents a flexible social arena, fostering a sense of curiosity, play, and tolerance.  The Kulturkorgen emerges as an outcrop from the hills of Gothenburg. Image Courtesy of Sweco The Kulturkorgen emerges as an outcrop from the hills of Gothenburg. Image Courtesy of Sweco  Presentation model of the Kulturkorgen. Image Courtesy of Sweco Presentation model of the Kulturkorgen. Image Courtesy of Sweco

Concept sketch. Image Courtesy of Sweco Concept sketch. Image Courtesy of Sweco  South and west elevations. Image Courtesy of Sweco South and west elevations. Image Courtesy of Sweco News via: Sweco Architects. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Ecotox Centre / Brunet Saunier Architecture Posted: 13 May 2017 10:00 PM PDT  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam

© Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam From the architect. Ecotox is a unique research centre in Europe. Designed like a projects' hotel, it welcomes international teams for projects on environmental toxicology and long-term ecotoxicology.  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam This device, innovative in its design, is a hyper modular tool that is very flexible in its adaptation capacity, enabling to house very different research projects from one another, with highly divergent technical and functional constraints.  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam Beginning of an urban character With close proximity to the Valence TGV station, the Ecotox Centre is the first building constructed in the Rovaltain ecopark. The project's aim is thus to offer a common identity for both the scientific community and the Rovaltain site.  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam To avoid the project's monumentality and linear façades out of proportion for this site, the project draws on the program's very motley constraints to create a play on volumes between the different platforms. The different buildings thus gathered make for a landscape of volumes, a mass ratio that constructs the image of the project and gives off dynamic perspectives.  Plan 01 Plan 01 Façade consistency The composition of the façade on the scale of a building follows a sedimentation process similar to that of the Vercors massif. Each building applies the same system that links an external insulation ensuring high thermal performances, a coloured metal cladding of which the tones echo those found in the surrounding landscape and a system of louvre horizontal panels that protects one from solar radiation while integrating all the ventilation systems and that offers great flexibility in its implementation. The irregular distribution of the horizontal blades answers to the specific requirements and constraints of the premises (offices, laboratories, technical spaces etc.) and offers for the Ecotox centre a visual interpretation that is unique and rooted in its surrounding.  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam  Concept facade Concept facade  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam An entrance sequence The only exception in the continuity of the panels, the tympanum of the entrance façade is a curtain wall (structural glazing system), screen-printed and linked to supporting shell beams on four levels. Highly exposed to solar radiation, this façade integrates a device of solar chimneys to ventilate in a natural way the conference room of 300 places.  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam On the garden side, pantograph openings let the fresh air enter from the garden while the hot air is evacuated to the roof through the solar chimney that is integrated in a façade symbolising the Ecotox Centre showcase.  Section Section In the continuation of the entrance court, and under the bleachers of the conference room, the entrance is a vast space without intermediary support points, completely open to the interior garden.  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam Real venue for exchanges and relaxation, at the crossroads of the scientific platforms, this open space organizes the internal functioning and benefits all the users of the centre.  © Edouard Decam © Edouard Decam This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| You are subscribed to email updates from ArchDaily. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar