Arch Daily |

- Spotlight: Walter Gropius

- Observation Tower Negenoord / De Gouden Liniaal Architecten

- Dinosaur Theme Park Entrance Building / rimpf ARCHITEKTUR

- The Shadow House / Samira Rathod Design Associates

- A Sake Brewery Addition / a-um

- Dongduk Women's University Centennial Memorial Hall / HYUNDAI Architects & Engineers

- OMA-Alumni NEUBAU Greenlighted for Pixelated Mixed-Use Complex in London

- Beach House / DX Architects

- Olive + Squash / Neiheiser Argyros

- Herzog & de Meuron's AstraZeneca R&D Headquarters Tops Out in Cambridge

- Cs House / Antonio Altarriba Comes

- Small Projects, Wide Reach: Hilary Sample on the Benefits of Maintaining a Purposefully Small Office

- Eco Moyo Education Centre / The Scarcity and Creativity Studio

- Zaha Hadid Architects Reveal Ecological Residential Complex for the Mayan Riviera

- 10 Years On, How the Recession Has Proven Architecture's Value (And Shown Us Architects' Folly)

- Alto San Francisco House / CAW Arquitectos

- 12 Libraries You Should Bookmark Right Now

- Forget Treehouses - Cliffhouses are the Future

- GS1 Portugal / PROMONTORIO

| Posted: 17 May 2017 09:00 PM PDT  Bauhaus, 1925. Image © Thomas Lewandovski Bauhaus, 1925. Image © Thomas Lewandovski One of the most highly regarded architects of the 20th century, Walter Gropius (18 May 1883 – 5 July 1969) was one of the founding fathers of Modernism, and the founder of the Bauhaus, the German "School of Building" that embraced elements of art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography in its design, development and production.  Walter Gropius with Harry Seidler in 1954. Image <a href='https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gropius_and_Seidler_by_Dupain_1954.jpg'>via Wikimedia Commons</a> (image by Max Dupain in the public domain) Walter Gropius with Harry Seidler in 1954. Image <a href='https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gropius_and_Seidler_by_Dupain_1954.jpg'>via Wikimedia Commons</a> (image by Max Dupain in the public domain) Like many modernists of the period, Gropius was interested in the mechanization of work and the utilitarianism of newly developed factories. In 1908, he joined the studio of renowned German architect and industrial designer Peter Behrens, where he worked alongside two people who would also later become notable modernist architects: Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.  Fagus Factory, 1911. Image © Carsten Janssen <a href='https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fagus_Gropius_Hauptgebaeude_200705_wiki_front.jpg'>via Wikimedia</a> licensed under <a href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/deed.en'>CC-BY-SA-2.0-DE</a> Fagus Factory, 1911. Image © Carsten Janssen <a href='https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fagus_Gropius_Hauptgebaeude_200705_wiki_front.jpg'>via Wikimedia</a> licensed under <a href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/deed.en'>CC-BY-SA-2.0-DE</a> However, of the three young architects at Behren's practice, Gropius was the first to put his Modernist ideas to work. In 1911, he and Adolf Meyer designed the Fagus Factory, a glass and steel cubic building which pioneered modern architectural devices such as glass curtain walls, and was built from the floor plans of the more traditional industrial architect Eduard Werner.  Bauhaus, 1925. Image © Thomas Lewandovski Bauhaus, 1925. Image © Thomas Lewandovski In 1919, Gropius took over as master of the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar, promptly turning it into The Bauhaus. From then until 1933, the school was one of Europe's most progressive and influential schools of design, greatly influencing the current of modern art and architecture. The Bauhaus in Dessau was designed in 1925 by Gropius, who distilled his teachings into architectural elements of the building.  Bauhaus, 1925. Image © Thomas Lewandovski Bauhaus, 1925. Image © Thomas Lewandovski Gropius also contributed with published writings, discussing the Bauhaus Manifesto, the role of the artist, and the artist's relationship to his or her work. After emigrating to the United States, Gropius continued his teachings and exploring the Bauhaus ideal. While teaching at Harvard University, he lived with his family in the self-designed Gropius House.  Gropius House, 1938. Image © <a href='https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gropius_House,_Lincoln,_Massachusetts_-_Front_View.JPG'>Wikimedia user Daderot</a> licensed under <a href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en'>CC BY-SA 3.0</a> Gropius House, 1938. Image © <a href='https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gropius_House,_Lincoln,_Massachusetts_-_Front_View.JPG'>Wikimedia user Daderot</a> licensed under <a href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en'>CC BY-SA 3.0</a> After its closure by the Nazis in 1933, the Bauhaus rose in popularity in the Western world with an exhibition, organized by Gropius, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. By the time Gropius died in 1969, his ideas on architecture and the Bauhaus itself had become a staple of modernist architecture. Check out all of Gropius' designs featured on ArchDaily through the thumbnails below, and our coverage of the Bauhaus below those: Beautifully-Designed, Downloadable Bauhaus Architecture Books Infographic: The Bauhaus, Where Form Follows Function Harvard Museums Releases Online Catalogue of 32,000 Bauhaus Works A Bauhaus Façade Study by Laurian Ghinitoiu VIDEO: Design in 6 Lovely, Digestible Nutshells Infographic: The Bauhaus Movement and the School that Started it All Bauhaus Masters' Houses Restored, Now Open to Public This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Observation Tower Negenoord / De Gouden Liniaal Architecten Posted: 17 May 2017 08:00 PM PDT  © Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin

© Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin From the architect. Negenoord is a former gravel extraction area (about 150ha), which is now transformed to a nature reserve called Maasvalley Riverpark, 2500 hectares in size and located on both sides of the Belgium-Netherlands border which is formed by the Maas river. The redevelopment also gives more space for the river creating a flooding area.  Site plan Site plan Our client for this project is a government organization who organizes the redevelopment of all former gravel extraction areas. The concept for the redevelopment of Negenoord focused on spontaneous nature development, natural education but also recreational use. In order to fully experience the area, a small observation tower had to be built on a small hill, located in the middle of the area and created to keep the tower safe from winter floods.  © Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin We created a building that was crafted with the local materials excavated from the Maas area: earth, clay and gravel. External walls were created with the rammed earth building technique. The surface area of these walls will slowly erode, so the gravel will become visible after a while. Inside, a central core with stairs is made out of concrete, which is sandblasted to show the gravel as well. Through its materialization, the building tells us about the location it's built. and becomes strongly anchored in its environment.  © Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin The climb to the top is conceived in different sequences. On each of the landings of the top 3 staircases a different view opens up to the environment. The triangular shape and the position of the cut-off corners was determined by these views.  Floor Floor The rammed earth building technique is thousands of years old and can be found in the whole world. Soil-damp earth gets poured in layers of 15cm into a formwork and is compressed mechanically to 12cm. The correct mixture of sand, clay and gravel makes it suitable for building load-bearing walls.  © Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin The tower is the first public earthen building in the Benelux region. the standardization of the building technique is still under development. For the moment, there are no standards yet and that makes it difficult to describe the technique for use in a public project.  Section Section To guarantee the quality of the construction, the design team was supported by an international team of experts: Cratterre/ Vessières&Cie/ BC Studies. The earth-consultants analyzed different local materials, tried different mixes and evaluated them on compression force, abrasion, color and appearance. The chosen mix consisted of 20% gravel, 40% ochre-colored earth, and 40% clay, stabilized with Trasslime. They also included a report on how to detail architectural design when building with Rammed Earth, as well as on how to organize the construction site for Rammed Earth Works.  © Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin During construction, workers were trained in mixing, maintaining right humidity in the mix, building formwork, ramming and removing formwork. Every week, field testing of humidity, and laboratory testing of compression force on specimens were done to monitor the quality.  © Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin The Rammed Earth works took 7 weeks. Around 20 m3 of rammed earth was done every week, working from staircase to staircase., to arrive at 11 meters high.  © Filip Dujardin © Filip Dujardin A short film about the observation tower, seen from the perspective of different characters, was made by Lotte Knaepen and Marco Levantacti This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Dinosaur Theme Park Entrance Building / rimpf ARCHITEKTUR Posted: 17 May 2017 07:00 PM PDT  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser

© Michael Moser © Michael Moser From the architect. The primordial cell and its division as the origin of life constitute the allegorized architect's plan for the entrance building of the theme park. Borrowed from the nature, the process of the mitosis is both, project idea and role model for the filigree construction and shaping, which is in a dialogue with the nature. In this context, bionic borrowings visualize the evolution of life.  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser Through cell division, the primordial cell has been transformed into the constructed, widely remarkable and significant MITOSEUM. As a result, primarily curious expectations are generated for the approaching visitor. The six phases of the mitosis, starting with the interphase, followed by the prophase, the prometaphase, the metaphase, the anaphase, and finally the telophase, were role models for the development of the design idea and can be retrieved within it. Due to its heights and volumes, the "cells" are visible from even a long distance.  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser The structure and color of the translucent shell, made of ETFE-foil, symbolize nature and life. The exceptional significance and the identity-establishing shape contribute to the character of this entrance building as an unique location.  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser  Construction Isometric Construction Isometric  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser Construction Site and Development The existing topography including the declining terrain is integrated into the staging of the visitor's approaching. The narrowing access route and the flanking lava rocks create an entrancing path. On this way, the elements of water and earth come alive until it finally leads through the building structure into the dividing cell. Here, the beginning of the theme park with the "Fire Gate" and the "Primordial Soup" is visible through the translucent membrane of the shell.  Floor plan Floor plan At the peak of the suspense, the visitor leaves the "real world" while approaching the MITOSEUM and steps into the evolution history of earth and life.  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser Organisation and Function Smooth and organic shapes inside the entrance building support the route guidance and make it intuitive. Therefore, the central foyer including the connected functions ticket office, shop, bistro, and the ancillary rooms is designed as intervening space between the cells. As connector of the different functions, it is derived from the ideal design and effective capability of the nature.  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser Construction The entrance level including bistro, shop, and presentation room is covered with three dome constructions. These domes are light structures and symbolize the "cells" of the mitosis. The nature creates genius, viable, and aesthetic shapes, which constitute role models for the realized dome membranes. Here, the borrowing of shapes and constructions from the nature are not plagiarisms, but necessary references to enable an intelligent, aesthetically ambitious and economical construction. The interior of the building is flooded with light through the transparent shell. While twilight and the after the connected inversion of light conditions, the cell membranes become luminous landmarks.  © Michael Moser © Michael Moser This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| The Shadow House / Samira Rathod Design Associates Posted: 17 May 2017 03:00 PM PDT  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner

© Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner From the architect. Set on the foothills of Maharashtra in Alibaug, far away from the busy city life of Mumbai. The plot was a dry barren piece of parched earth. When I first saw it, there were two lonely trees; a view of the hills in the distance and dry fields all the way to the sky, all around.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner In that scorching heat, there was only one desire- to be lulled back into that familiar dark, cold, calmness.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner The courtyard house of southern India does this well, with its overarching low slung roofs and a central courtyard around which the rooms surround. The idea of the house began here.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner This house is carefully sited between the two trees, grazing its walls into its crown; its three bedrooms, and living spaces surround an half bounded courtyard with a sliver that opens into a small plunge pool; indigo blue water, that spouts out gushing waters. Its sounds making for cooling delight.  Sketch 3 Sketch 3 The courtyard is marked with a the babul tree for shade, which as it would grow would engulf its entire space and suffuse the house with its blazing fragrance and a confetti of tiny white flowers every morning.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner Architecturally the courtyard doesn't open to spaces, but instead, to a broad corridor that works like a woody bridge holding a study, under a sweeping corten steel roof and ties all the upper rooms into a single floor.  Ground Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan But the sun is unforgiving; its screeching light needed to be quietened with shade and shadows. From here, emerged the language of its tectonics, both for its architecture and landscape.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner As one enters the house, the long walk from where the car leaves you, in between walls of tall grasses brushes against the skin, and a carpet of rolling green mounds that form a seamless edge to the site.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner The house is conceived in shredded layers, as it unravels spaces, each rendered in a different intonation of light. The first of its layers, on the southern side, is a thick, dead, colored concrete wall -a heavy thermal curtain to ward off the heat.  Section BB Section BB The second layer is the corten steel pitched roof over the woody bridge, holding the study area with windows like piano keys, alluding to old homes in the hills of Northern India.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner The stairs and its sliced wooden railings, the bridge held by the steel portals the accordion windows of the living room, legs of tables, the flooring patterns, and soft cotton sheers, all form a larger subset of overlapping layers.  Section AA Section AA Its every element is designed and detailed as if to obstruct light; shredded. The house is designed like a sieve through which light is filtered, dappled and draped into its hollows.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner The architecture is crafted as art, where conventional modes of building thought are deviated to deride the predictable strict geometries that are attached to impressive architecture.  First Floor First Floor The entire flooring, in contrary to orthogonal patterned alignments to the building, is worked upon like a feely painted canvas with various pigmented handmade concrete tiles. Light from the skylights slash the walls, painted in shades of brown.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner The living experience is designed to be gentle; dark, quiet and erotic, with its hierarchy of volumes and spatial textures. Steel, concrete and wood are choreographed to manufacture shadows and intrigue. In the mood for love; The shadow house.  © Edmund Sumner © Edmund Sumner This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| A Sake Brewery Addition / a-um Posted: 17 May 2017 01:00 PM PDT  © Nacasa & Partners © Nacasa & Partners

© Nacasa & Partners © Nacasa & Partners From the architect. Located in the midst of rice fields at the foothill of Mt. Sefuri in Itoshima-area, Fukuoka, Japan, SHIRAITO Sake-Brewery has marked its 160th brewing year in 2015, when the new additional architecture has completed.  Courtesy of a-um Courtesy of a-um In the site, this complex iscomposedwith number of buildings. This project was to design a new addition (partially re-construction) to its complex. Brewery workers move between building to building along its process of sake-making. The purpose was to obtain more space and to add new facilities to enhance the quality of their product. Most of the existing buildings in the site are very old and traditional. The "main" building is more than 100 years old. One of the task in design process was to connect historical buildings and the new addition not only functionally, but, of course, visually.  © Nacasa & Partners © Nacasa & Partners The traditional Japanese building at the site is very iconic.The concept of the new was to make a new tradition of Sake brewery. Since the traditional complex creates its "silhouette" with the triangular roof shape, overlapped, the new volumed was intended to be overlapped with triangular-shaped volume to cast new "silhouette" in modern way. And the concrete surface and structure possess the strong feeling visually and spatially, which the old one also has.  © Nacasa & Partners © Nacasa & Partners  Plan 1 Plan 1  © Nacasa & Partners © Nacasa & Partners The new addition is constructed with cast-in-place concrete structure and the entire building is covered with its concrete texture as exterior and interior finish. Since the program, sake brewery, requires sunlight-less space in order to protect product from sunlight, most of the rooms have no window, except the staff room and the washing room. And this creates the massive figure, which is iconic as a Sake brewery. The new and the old are structurally disconnected while its function connect the entire space as one complex.  © Nacasa & Partners © Nacasa & Partners This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Dongduk Women's University Centennial Memorial Hall / HYUNDAI Architects & Engineers Posted: 17 May 2017 12:00 PM PDT  © Bae Jihun © Bae Jihun

© Bae Jihun © Bae Jihun From the architect. The construction plan of the centennial memorial hall of Dongduk Women's University was started from the concept of 'Harbouring Daylight, Wind and Nature into the Learning'. Comfortable educational spaces were provided by voids that penetrate into a building and enable natural light and ventilation. Nature spaces like small gardens around the campus were created to be used as 'another classroom'. Also visitors can easily perceive their destinations through the voids inside the building and access th their destinations by the main stairway with ease. Characteristics of educational spaces such that students get together and scattered in a short time were reflected.  © Bae Jihun © Bae Jihun Daylight, Wind and Nature Arranging the rectangular building corresponding to the main direction of the wind and developing the road of the wind by voids, natural ventilation was actively induced. And in order to secure sufficient sunlight, the roof of the building was open to the air. The building provides comfortable spaces for research and study by bringing the sunlight, the wind, and the nature deeply into the building. It would be thought that the elements of passive design were transformed into a morphological concept.  © Bae Jihun © Bae Jihun Garden & Place Large and small open spaces were planned inside and outside of the building. Transforming the purpose of the educational facilities from research to complicated social activity and cultural exchange, students can learn about theoretical knowledge as well as social experience in the university. Therefore, the university placed small gardens and social areas where students get together around the building for students to response various activities.  © Bae Jihun © Bae Jihun Grand Stair Main stairway in the center of the building's void was planned as main vertical flow of human traffic, and every entrance installed at each floor help visitors to access to spaces horizontally. Pedestrian sequence from the entry garden to the roof garden by stairway provides various spatial experience and panoramic view, and it could become the center of interaction and communication of students.  Diagram Diagram This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| OMA-Alumni NEUBAU Greenlighted for Pixelated Mixed-Use Complex in London Posted: 17 May 2017 10:03 AM PDT  Courtesy of NEUBAU Courtesy of NEUBAU Emerging practice NEUBAU has received planning permission to begin construction on Tower Station, a mixed-use residential building located on Fincheley Road in London. Commissioned by County Tower Properties, the 'pixelated' building will be located on the site of a former gas station and clock tower, replacing the previous use with a new mechanical clock at the building's peak, creating a new local landmark that echos the site's history. This is the largest commission to date for NEUBAU, founded in 2014 by former OMA architects Brigitta Lenz and Alexander Giarlis.  Courtesy of NEUBAU Courtesy of NEUBAU 'This project is the result of an intense collaboration with a highly-motivated team and a visionary client, whose dedication to a design-focused approach made possible much that this industry usually sacrifices in the name of profit – it presents an exciting opportunity for a landmark site to be developed to its full potential, and we are keen to take things forward," said Brigitta Lenz, co-director of NEUBAU.  Courtesy of NEUBAU Courtesy of NEUBAU  Courtesy of NEUBAU Courtesy of NEUBAU Tower Station will contain a total of 28 six-meter-wide apartments, stacked to break down the overall mass of the building and reduce its visual impact from the street. Fully glazed exterior facades will provide residents with views of the surrounding area while flooding each unit with natural light. Shielded from street noise by the building mass, a pocket garden at the rear of the structure will offer residents a large shared space for planting, including a vertical garden that will climb up the complex's inner walls. Winter gardens at the each level will offer private open spaces alongside the communal garden, creating "the feeling of a private oasis for residents."  Courtesy of NEUBAU Courtesy of NEUBAU "The design of this project was a journey across many boundaries and in search for a language that could overcome the neighborhood's historically pastiche architecture on a landmark designated site – to add a clock atop a residential building was integral to the scheme, and aims to preserve a significant local memory of the service station's old clock tower," adds Alexander Giarlis, co-director. The project is slated for completion in 2019. News via NEUBAU.  Courtesy of NEUBAU Courtesy of NEUBAU  Courtesy of NEUBAU Courtesy of NEUBAU

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 17 May 2017 10:00 AM PDT  © Aaron Pocock © Aaron Pocock

© Aaron Pocock © Aaron Pocock From the architect. The Blairgowrie Beach House on the Mornington Peninsula retained and altered the rear proportion of the existing building and expanded the dwelling forward on a steeply sloped site to accommodate additional living and sleeping areas.  © Aaron Pocock © Aaron Pocock Manipulations of the building form were employed to address the access disconnect and setup a conceptual framework where we continued our practices interest in spatial division patterns.  © Aaron Pocock © Aaron Pocock  Section Section  © Aaron Pocock © Aaron Pocock The new first floor incorporates a large cantilevered metal clad form which created a covered area for car parking, and was counteracted with concrete rendered vertical walls which pushed out to level out the land. Continuing formal manipulations, the metal clad form had volumes carved out to incorporate a balcony space, and a feature vertical window to illuminate at night and interact with the public realm when the house is being occupied.  © Aaron Pocock © Aaron Pocock This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Olive + Squash / Neiheiser Argyros Posted: 17 May 2017 08:00 AM PDT  Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros

Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros From the architect. The project, for a start-up salad and slow food café in the City of London, has a split personality - it is a space that both accommodates our frenetic work rhythms and invites us to slow down. It is a cafe that serves slow food fast, celebrating its locally sourced ingredients. The architecture therefore has two tasks; to address multiple speeds of engagement, and to provide a neutral framework that foregrounds the various shapes and colors of the vegetables, herbs, fruits, and grains on its menu.  Diagram Diagram The space is asymmetrically divided in half, with a take-out counter adjacent to the street below, and a dining room in a newly constructed mezzanine above. The space below is neutral, cool, and hard, allowing the bright colors and geometries of the raw produce to be the primary material. Above, the palette is warm, textured, and soft, inviting visitors to gather and linger over their meal.  Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros To physically divide, but visually connect these two distinct spaces Neiheiser Argyros have constructed a white metal grid. A contemporary echo of the traditional farmer's trellis, the grid hosts plants, flowers, herbs, menu signage, and integrated seating. This simple device articulates multiple spatial relationships in a single gesture; defining the primary spaces, framing views, curating movement, and providing a defining identity for the store.  Diagram Diagram We designed a custom-formed terraced corian counter-top for the servery display which is always facing the customer. While all the ingredients are displayed together in three terraced rows, we wanted each one's color and texture to stand out. We therefore carefully calibrated the spacing between each ingredient with white corian infills, visual gaps that allowed each ingredient to read independently from the rest of the group.  Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros Courtesy of Neiheiser Argyros This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Herzog & de Meuron's AstraZeneca R&D Headquarters Tops Out in Cambridge Posted: 17 May 2017 07:30 AM PDT .jpg?1495045916) © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca The Herzog & de Meuron-designed global corporate headquarters for pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca has topped out in Cambridge, UK, as the building pushes forward to a series of opening dates beginning in 2018. Developed alongside AstraZeneca researchers and executive architect/lead consultant BDP, the scheme consists of a ring-shaped volume containing a series of open laboratories and transparent glass walls intended to foster the company's principle of collaboration across disciplines.  Courtesy of BDP Courtesy of BDP "I would like to congratulate AstraZeneca along with the design and construction teams, on successfully reaching the Topping Out milestone of the project," said Pierre de Meuron. "We have assessed the achievements in the construction very highly up to now, and are confident that what remains ahead of us will be done with passion from all parties, to successfully complete this project." .jpg?1495045871) © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca "The architecture supports AZ's ambition to be a key point of exchange and collaboration in the CBC community, and makes it visible with a porous building that is accessible from three different sides. The new site will bring AstraZeneca scientists together with those from its global biologics R&D arm, MedImmune, working side-by-side under one roof." .jpg?1495045929) © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca .jpg?1495045890) © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca The new complex within the company's Cambridge Biomedical Campus (CBC) will contain both R&D facilities as well as the global corporates office. A continuous walkway along the ring's perimeter will serve as a core circulatory artery throughout the building, while a central courtyard will create a space for relaxation and informal meetings. Upon completion, the site will house scientists working on the treatment of respiratory, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases, as well as become AstraZeneca's largest facility for oncology research. .jpg?1495045904) © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca .jpg?1495045944) © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca The building's topping out represents the completion of the building's concrete structural frame, with construction now turning to installation of the saw toothed roof, external glass cladding and the internal fit out. News via AstraZeneca, BDP.  © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca © Herzog & de Meuron. Courtesy of Astrazeneca This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Cs House / Antonio Altarriba Comes Posted: 17 May 2017 06:00 AM PDT  © Diego Opazo © Diego Opazo

© Diego Opazo © Diego Opazo From the architect. The Cs House is placed on a plot in 2 levels, long but narrow, which is accessed by its north side.  © Diego Opazo © Diego Opazo As a condition of the project we had, on the north side, at a height of 3 meters above the ground level, the views of the "Sierra Calderona" mountain, while the East and West sides were occupied by other plots, leaving the south view free of obstacles.  Section Section The idea is to "occupy" the plot with a series of volumes, colonizing the plot in its longitudinal axis, being placed in such a way that all the spaces have double ventilation. This double glazing makes possible the viewing of the whole plot from the access to its final limit, where the outdoor pool is located.  © Diego Opazo © Diego Opazo This are the spaces of the house: Basement: Garage, living room, bedroom with bathroom, indoor swimming pool and technical room.  Basement Basement Ground floor: Guest room, bathroom, kitchen, laundry room and living room.  Ground Floor plan Ground Floor plan First floor: 2 bedrooms with bathroom and master bedroom with "in suite" bathroom and dressing room.  First Floor Plan First Floor Plan The intention is to relate all spaces with each other, both externally and internally, including the basement level.  © Diego Opazo © Diego Opazo That's the reason why the volumes are distributed around a "patio" that lets the garden to enter the house, seeming to be infinite thanks to its visual relationship.  © Diego Opazo © Diego Opazo The materials used in the building are glass, limestone, and corten steel, both of them visually related by the use of a similar cutting pattern.  © Diego Opazo © Diego Opazo This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

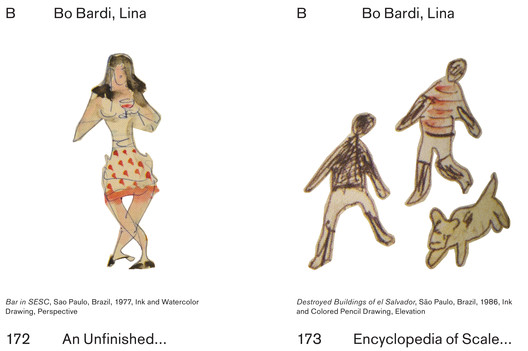

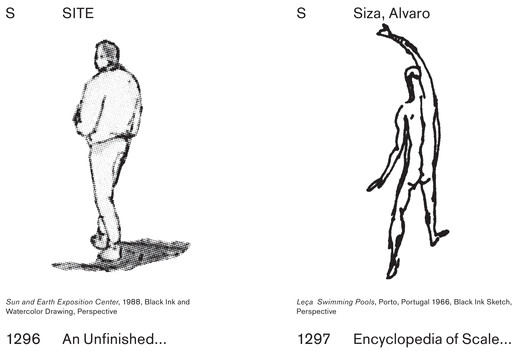

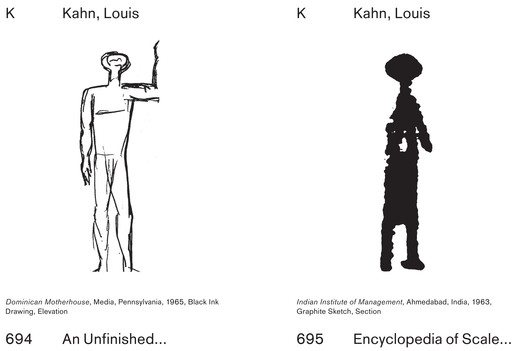

| Small Projects, Wide Reach: Hilary Sample on the Benefits of Maintaining a Purposefully Small Office Posted: 17 May 2017 04:30 AM PDT  MOS Architects, "Selfie Curtain" – 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "Selfie Curtain" – 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial. Image © MOS Architects In the seventh episode of GSAPP Conversations Amale Andraos speaks with Hilary Sample, an academic and co-founder of MOS Architects alongside her partner Michael Meredith. They discuss the lasting influence of ORDOS 100—a collection of villas built in Inner Mongolia by emerging and renowned practices—on the firm's thinking, the role of representation, and how Sample's practice pursues an inclusive way of working and thinking – while maintaining a purposefully small office. GSAPP Conversations is a podcast series designed to offer a window onto the expanding field of contemporary architectural practice. Each episode pivots around discussions on current projects, research, and obsessions of a diverse group of invited guests at Columbia, from both emerging and well-established practices. Usually hosted by the Dean of the GSAPP, Amale Andraos, the conversations also feature the school's influential faculty and alumni and give students the opportunity to engage architects on issues of concern to the next generation.  GSAPP Conversations #7: Hilary Sample with Amale AndraosAmale Andraos: Hi, Hilary. Thank you for joining me today. I think one of the aspects of your practice with MOS is that it is redefining practice and how architects today can engage in thinking about architecture across scales. Clearly you've become a kind of model for the next generation of architects and for students alike. Do you want to tell me what you're working on right now that's exciting? And what has been your thinking in terms of creating a practice that is both engaged, but also engaged with the discipline at a more in-depth perspective? Hilary Sample: Thanks, Amale, for having me join in this conversation. I think we are coming up actually on ten years of having the office, so that's a fair amount of time. And in a way I think we've stayed pretty true to our beginnings, when we started around a big table. We still sit, relatively, all together around that table. We're about five people plus Michael [Meredith] and myself, so we're very small – and purposefully small. I think there's not a specific ambition to grow in terms of numbers or these things that American offices tend to be categorized by. For better or for worse, I think American offices tend to start with single-family houses. There's been a shift in that now, but when we started our office we were really working on just one project and then started to think about how we could take that into other aspects like making objects. And while we've gotten some attention recently for things like books or the Selfie Curtain, these types of tangential projects have always been part of our thinking, our work and interests, and of how we could start our office through these different scales even if we were only actually building at one scale - at that time a house. That's something we're thinking about continuously, and working through this different set of objects, of representations, helps us to reframe architecture for ourselves.  MOS Architects, "Selfie Curtain" – 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "Selfie Curtain" – 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial. Image © MOS Architects  MOS Architects, "Selfie Curtain" – 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "Selfie Curtain" – 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial. Image © MOS Architects And coming out of a period where we're facing all these different camps – there's been such a fragmentation of the discipline – we didn't want to have to pick or choose. And maybe not falling neatly into one category creates certain problems for a practice, but we tried to be very inclusive in our work and in our thinking. In the same way that we try to make things and be a creative office, it's also about producing a certain kind of culture within that office. This is as much of a project as the work itself, that we can support those different explorations. And then, hopefully over time these things come back and reinforce each other into something that we've liked to talk about lately, which is the body of work in the office. AA: I think that's really visible through your latest monograph, Selected Works. And what's interesting about the book is the work of course, but also the office part – the office manual, which clearly indicates an interest of a new generation of architects in not only practicing, but designing the creative practice. This is the moment when we have to rethink what the office is. So when you declare that you don't really have the ambition to grow so much bigger and you resist the pressures of the market to be a certain scale, either too small or too big, it is already an act of design of the practice, which I think is really interesting. It takes a very strong position to declare, "This is where we are now." Even if the pressures are moving you in a different direction. It always seems to me that you're re-assembling architecture. You're collecting all these pieces and putting them back together in a new way. So it's very inclusive, but it's not an expansion that moves you away from architecture. It's an expansion that then folds itself back on itself to re-enter architecture on your own terms. And one of those terms, both in your practice and in your teaching, has been the question of representation as a hinge to reenter the discipline. Do you want to talk a little bit about representation in your practice, but also how you're bringing that as a main focus here at the school? HS: Yes, we also talk about this together all the time in thinking about the school and our own practices. Probably one of the most important moments in the office's work had to do with ORDOS 100, this project that you and Dan [Wood with WORKac] were also a part of: a collection of houses in Inner Mongolia that were essentially clientless. And it was also a very large-scale project, much larger than anything we had worked on in our office, at least in terms of a house.  MOS Architects, "Lot No. 6" – 2008. Proposal for Ordos 100, Inner Mongolia. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "Lot No. 6" – 2008. Proposal for Ordos 100, Inner Mongolia. Image © MOS Architects  MOS Architects, "Lot No. 6" – 2008. Proposal for Ordos 100, Inner Mongolia. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "Lot No. 6" – 2008. Proposal for Ordos 100, Inner Mongolia. Image © MOS Architects And without a client, at this big scale, we had to reconcile those things and produce an architecture out of it. One of the ideas that came out of it was to make a video and invent characters that would live in the house. We constructed this life around these characters to give a reason for why we would be designing something, because it was not given to us. This is usually not the typical case, it was much more of academic project in some ways. And from there we really started to push further on this idea of a variety of representations. This is something that was very different from our training in school and undergraduate, where there was a certain set of figures we were to look at and a certain way of drawing. It was very limited before the computer and I always like to say we're self-taught in that sense. I think that idea of coming to different technologies on our own produced a certain ethos and a certain culture. And maybe today it's not that different in some ways for students, partially because there are so many choices. At your core you still have to have a sense of curiosity and a sense of wonder, but also a sense of pursuing something very specific - even if you change your mind later. These things are not necessarily so prescriptive and taught, but emerge in combination with global experiences, which I think ORDOS was for us. So it was interesting to think about representation through a global project somehow, if that makes sense. AA: Yeah, it makes sense in that we were given a so-called desert declared as a lack of context. But of course there were so many other contexts that were layered: the existing context, the desert, the ecology, predicting the people who were going to live there, and then the context of all these architects together and their conversations. And I think that the kinds of constructions that you built around that project, using representation as a hinge between discourse and practice and as a way to reenter the project was really interesting. And this idea of who the subjects are that you're constructing through your work has been a thread that the scale figure book is now making really visible. Who are these scales that architects are putting in their buildings? Suddenly it's no longer just about the buildings, but about these figures. You lead the Housing Studio here [at Columbia GSAPP]. It is always so interesting to continue to think about housing today – housing having constructed so many different subjectivities – and to invite students today to think about housing globally. You travel with the students and you compare typologies and scales and different contexts – cultural but also geographic and environmental. And through the lens of housing this conversation has started to result in really interesting ways to enter various cities and contexts. And so in the same way you use representation and invite the students to use representation as a hinge between discourse and practice, it seems to me that you're using housing to create a new hinge between architecture and the city – but no longer just the city, but different cities and different contexts. You were in Mexico for the last housing trip [in November 2016], and I was on the other side of the so-called wall at the time of the elections, and it probably was a really interesting moment. I wanted to hear a little bit about how you think the students are re-engaging this question of housing today.  MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Nicholas Hawksmoor. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Nicholas Hawksmoor. Image © MOS Architects HS: The Housing Studio here at Columbia GSAPP is one of the oldest ones as a curriculum or pedagogy within the school, and within architecture very specifically. It's not something that is placed into urban design or urban planning, because of course housing can operate at that scale of thousands, of tens of thousands of units like in The Netherlands, for instance, which has a national housing plan. So you have to defend housing in a way for architecture because it does have that capability to be on such a large scale. If you reduce it down to something small, it becomes a single-family house and that's a whole other kind of disciplinary problem. So for me it's exciting to think about housing in those terms, of having to hold this ground between these two incredible ranges in terms of density, politics, economy, culture, and the representation of those things – which are also things that we look at in the studio. At the school it's been taught for something like 45 years, and it came out of two exhibitions at MoMA in the late '60s, early '70s. We have incredible faculty who have been doing research on housing for a long time: of course Richard Plunz and Gwendolyn Wright, just to name a few. Reinhold Martin at the Buell Center is doing other projects around it. So there's not only housing happening in the design studios, but I think we have incredible support for housing that can be explored beyond the studio. These things are fantastic to reinforce each other and certainly have been helpful to me as a teacher in thinking about the studio's direction.  MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Lina Bo Bardi. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Lina Bo Bardi. Image © MOS Architects And doing housing in New York City, we can't escape an incredible history of housing here within Manhattan. From some that are not necessarily so positive – if we think of NYCHA and the condition that it's in right now including all of the deterioration and the problems as an organization – to other more contemporary projects that are being built in the city and try to serve as new models. So we have those two spectrums of housing, one very optimistic, one pessimistic, and it can be very tough to work between them. But ultimately New York is a place that imports many models and types, and so I wanted to look further at the influence onto the housing situation in New York. To parallel that and also reflect the incredible diversity of our student body, I asked that we start to look beyond New York for examples. And that led to thinking about housing as a global problem, not just a New York problem. But also to look at these two simultaneously, which then inherently produces a variety of differences in politics and economics and culture and so on for the studio. And these things are very interesting for the students. We spend a lot of time looking at examples and precedents and going out in New York and seeing projects, but then also taking trips. So on November 9th we were in Mexico City, the day after the election, and it seemed like a very surreal moment. But we saw an incredible range of projects and started by looking at Luis Barragan's own house. I thought that was very important for the students, to see a project that they would study by someone who is also a landscape architect, and to get a sense of what that means in terms of a relationship to a house.  MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Alvaro Siza Viera. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Alvaro Siza Viera. Image © MOS Architects And then we also had an incredible experience of visiting Mario Pani's housing project, one of the first social housing projects in Mexico City, where the residents have now taken over and essentially manage the property. It's all connected, something like 800 units, in the form of a zigzag. And we walked through the whole building – they have planter boxes with plants, residents are growing rosemary and things for their garden, it is the delicate everyday experience up against a massive project. So it's something very real, but brutal at the same time. And this kind of incredible dialectic that housing can produce was so compelling for the students. AA: I've seen some of the results in the students' recent work. Not only is there so much invention in terms of representation; it's more playful, there's an attention to detail, to the human scale, and a sort of anti-spectacle tendency which is quite refreshing. There's tremendous invention, for example a handrail that is separating the stair from the living room. I think the students are really re-engaging that level of reality, and projecting themselves. There isn't the sort of abstraction that housing has at times produced. I can't help but think that it's somehow a result of your pedagogy and the kinds of relational thinking and experiences that they are living as they travel to Rio or Mumbai and also get a sense of what housing means today across these various contexts.  MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Louis Kahn. Image © MOS Architects MOS Architects, "An Unfinished Encyclopedia of Scale Figures without Architecture" – Louis Kahn. Image © MOS Architects We're coming close to the end of the spring semester and are graduating a new year. I wanted to hear your thoughts and words of wisdom for your students who are graduating, and what we hope to give them here at the school as a toolbox of thinking and skills to engage in new ways to practice and other ways to approach architecture. So, what are you telling your students now? HS: Well, one of the things that I think is so important about the school—and what I think the students look for when they come here—is this sense of being global citizens and being part of a collective. Even though we're in this incredible culture of individuals and individuality, with the idea of constantly taking selfies. And that was one of the things about the Selfie Curtain for instance, that we were interested in how all of a sudden this collection of figures could become a place of interaction with friends. It wasn't just about yourself alone, let's say, but referencing and experiencing something with other people. At the heart of the Core, which is the primary thing I am teaching at the School, is that the students are thinking about how they are part of a collective, not just an individual. I think that's been a big shift for the practice of architecture. It's of course about finding your own identity within that, but also about how you really exist within a much broader realm – making architecture on one hand for yourself but also for others, and to think about that as a way forward. We draw buildings, but we also draw people. But to give that kind of very important sense that architects are and should be responsible somewhat for a complete identity as an architect. And now more than ever we have the power to be global, not so much in creating work that is a spectacle in itself—I think we're beyond that—but in how we are as individuals in the field and how we produce a unifying collection, aggregation of ourselves. That's part of our role going forward at this moment in time I would say. AA: Thank you so much Hilary. I'm looking forward to seeing the work of your practice, but also the students' work. And I know that it's always really exciting to see this commitment to thinking through architecture across these areas. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Eco Moyo Education Centre / The Scarcity and Creativity Studio Posted: 17 May 2017 04:00 AM PDT  © SCS © SCS

© SCS © SCS From the architect. Eco Moyo is an educational Community Based Organisation located in Ezamoyo in Kilifi county, Kenya, providing free Montessori based education to children from poor families. Eco Moyo have recently bought a 5 hectares site half an hour drive from Kilifi town center. The site has a house, and Eco Moyo is building the infrastructure necessary to make it usable as an education centre.  Render Render During 2017 they built living accommodation for 20 pupils and for the teaching staff so that they can move operations to the new site. The development plan for Eco Moyo Education Centre consists of two parts: The first is Eco Moyo Primary School which is modelled on Green School Principals and the Montessori Education Method, emphasis is on practical approaches to each subject together with ethics, ecology, training in individual thinking and communication skills.  © SCS © SCS The second part is Eco Moyo Farm which will be based on Permaculture Principals for the cultivation of food crops, timber and animal husbandry. The goal is to meet the consumption needs of students and staff, while functioning as a demonstration site for locals and visitors. Eco Moyo have asked The Scarcity and Creativity Studio, AHO to design and build two classrooms on their new site. The Scarcity and Creativity Studio (SCS) spent 5 weeks in Eco Moyo building two classrooms for 20 students each, with adjoining pergolas which shade outdoor teaching areas.  Classrooms Floor Plans Classrooms Floor Plans Materials used were coral stone blocks rendered with 1:12 parts cement and local earth. To the back of each classroom a 'light wall', which is built of planed softwood, allows for ventilation and the controlled penetration of natural light. The roof trusses are built with softwood and covered with corrugated metal sheets. The roofs drain all rain water into two large water tanks to the back. A fabric ceiling (not yet installed) hung under the trusses will stop radiation from the metal roof sheets from reaching the occupants.  © SCS © SCS This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Zaha Hadid Architects Reveal Ecological Residential Complex for the Mayan Riviera Posted: 17 May 2017 03:45 AM PDT  © www.mir.no © www.mir.no Zaha Hadid Architects has revealed plans for a new ecologically-considered development located on a lush site along the Mayan Riviera in Mexico. Known as Alai, the complex will offer a nature-focused living experience while preserving a large portion of the forested site for species restoration.  © www.mir.no © www.mir.no Since the turn of the century, the Mayan Riviera has grown into one of the most important touristic regions in Latin America, welcoming more than 20 million arrivals last year. Matching this growth, the residential population of the area has nearly doubled since the year 2000, turning the natural paradise into an important center for business. This popularity has created the need for new development that can accommodate a large number of people, provide an engaging design experience, and preserve the natural ecological conditions for years to come. Located on a site already prepared for construction of a never-completed complex, Alai plans to adhere to these principles by limiting its combined footprint to less than 7% of the site's total area, creating a haven for the site to return to its natural state.  © GrossMax © GrossMax  © ZHA © ZHA An botanical nursery will contribute to the restoration of species on site, with plantings following a plan conceived in conjunction with landscape architects Gross Max. In addition to the regrowing schedule, a woodland nature and a coastal wetland reserve will be create to protect existing species such as the lagoon mangroves. These reserves will also become an attraction for visitors, made accessible by suspended footpaths that reduce impact on the ground. The residential buildings will be connected by an elevated platform containing amenities for sport and leisure and wrapped in a perforated facade that will allow natural light to penetrate into the spaces. By raising the podium nine meters above the ground, local wildlife will be able to continue traversing the site without impediment, while residents will be treated to views of the treetops and the coast beyond. Four different apartment typologies, each with their own private balcony, will provide residents with a range of living options and views to the Caribbean Sea or Nichupté Lagoon, while maximising the ability of the onshore trade winds to provide natural ventilation for the units.  © www.mir.no © www.mir.no The architects explain:

News via Zaha Hadid Architects.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| 10 Years On, How the Recession Has Proven Architecture's Value (And Shown Us Architects' Folly) Posted: 17 May 2017 02:30 AM PDT  © <a href='https://www.flickr.com/photos/backkratze/3482233639/'>Flickr user backkratze</a> licensed under <a href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/'>CC BY 2.0</a> © <a href='https://www.flickr.com/photos/backkratze/3482233639/'>Flickr user backkratze</a> licensed under <a href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/'>CC BY 2.0</a> This article was originally published by Common Edge as "Building Madness: How the Boom and Bust Mentality Distorts Architecture." Architects are economically bipolar; for us it is either the best or the worst of times. And it's not just architects. The entire construction industry is tuned to these extremes, but only architects are psychologically validated by booms and crushed by busts. All professions have a larger source of dependency—medicine needs insurance, law needs the justice system—but the construction industry has a starker equation: building requires capital. Contractors tend to react to market flows in purely transactional ways. Booms mean more work, more workers, more estimates, business expansion. For architects, a boom means life validation. Every architect wants to make a difference, and many want to offer salvation, like the architect Richard Rogers, who once said, "My passion and great enjoyment for architecture, and the reason the older I get the more I enjoy it is because I believe we—architects—can affect the quality of life of the people." But salvation can only be earned if buildings are created. When the economy tanks, it fulfills our worst fears, reinforcing the realization that what we do requires two things, independent of our work: money and faith. Architects always have faith, but clients only have it when they're flush. Like most fine arts, architecture surfs on the money available to fund it. Maybe the last decade can teach us something. Ten years ago, architects—especially residential architects—were giddy. We've always responded to the free market roller coaster—it's endemic to the profession—but in 2007 residential architects were at the center of a juggernaut. Unprecedented growth in home building overrode the usual cycles of supply and demand. So, for a brief period, the building of the American Dream dominated the world's economy. Magazines, new media, institutions, entire marketing efforts, were based on this phenomenon. The popping of this mammoth bubble in 2008 changed everything. The U.S. economy lost $14 trillion in economic activity from 2007 to 2009. The housing markets in places like Las Vegas and Phoenix went from boom to depression. Michigan, California and Arizona saw homeownership decline by more than 20% after 2007.  Courtesy of Common Edge Courtesy of Common Edge This was nothing new. I am old enough to have ridden through four previous crashes since entering the profession in 1978, during the Jimmy Carter Gas Crisis (remember those lines?). In the insanity of those economics, this translated into mortgage rates in the high-teens. A lot less design happened because far fewer buildings were financed. A handful of years later, I experienced the excitement of the Reagan Revolution, when McMansions began flooding suburbia. A stock market crash in 1987 put a hold on that. Rebound was swift and sure in the late 1980s, until there was a Savings and Loan Crisis. Then new technology helped the economy rebound. A huge influx of venture capital followed the digital revolution that created internet websites and net-based businesses. But in the early-aughts, early online enterprises failed to generate revenue, so venture capital vanished and the tech bubble burst. Then came the great American House Boom. But unlike the other booms, this was a tidal flow that elevated residential designers beyond any objective value. This boom was located directly in architecture's wheelhouse: it grew to three million new homes a year and helped lead the economy through the tech collapse. Home values outstripped the stock market as a wealth creator for the middle class; ownership reached a record 69% of adults. Everybody was fully engaged and making money, because a common good, the buildings we lived in, was part of a government-backed, bank-enabled effort at universal home ownership. Eventually the profit motives of banks and bond markets overwhelmed the realities of cost and value. In some markets, you could buy a wreck, add paint and pansies and make five figures in five months. Even though residential architects designed a tiny percentage of new and renovated homes, self-declared residential architecture firms almost doubled as a percentage of the American profession: trending to 20% of all firms, up from about 10%. Once again, architects were shot out of the economic cannon: we were benefitting from circumstances that we did not create. Unlike all those other booms, however, this one was built on a foundation of deceit and exploitation. There were predatory lenders, lying agents and profit-driven market gamers, and their larceny could not go on forever. Without a greater-than-inflation value explosion in homes—the rocket fuel that fed the boom—the market crashed to earth. For the first time, a building type in one market, the American home, helped wreck the world economy. The stock market crashed, unemployment spiked, and spec building ground to a halt. The first seven years of the 21st century offered a tsunami for us to surf upon. Architects were wiped out in the subsequent flood. Again. Why? It's personal. If architects valued helping people to build what made sense, they would create a microeconomy of value that is less subject to boom and bust. Doctors work on every illness, not just the glamorous and paying ones; many lawyers help those who are in trouble. Architects need to know that our culture can value design at any level, and not gorge on the crazy hubris exclusive to booms. The busts should teach us that. When the housing market crashed, we saw an astounding 90% reduction in new homes. That starvation reality is virtually unheard of in other industries (even buggy whip manufacturers had a generation to go bust). Architects often believe that in booms the truth comes out and our real value is revealed; in busts, we all-too-quickly become irrelevant. We seem unable to realize that neither is true: the rush to build is not a reflection of our inherent value; but neither is the absence of building proof of our irrelevance. Our value, to clients and to society, is timeless: design is a necessity in every market. Building booms are self-justifying, but the fulfilled lust often compromises the value of architects, beyond design. During flush times, it's easy to accept huge price tags and expedient builders. When you're in love, your judgment is impaired. Why do we do this to ourselves? Building is an elemental human act. This last decade of change, this reset of the architecture profession, has radically increased productivity while decreasing job opportunities. But, for me, this doldrum decade has done something else; it has reinforced my belief in our usefulness. We provide a service that has value, regardless of economic climate or cost. Of course we are form-givers, innovators, even aspiring Master Builders, but after a 10-year crater, we survivors know better than ever that architecture is first, and always, a service. We have unique knowledge, creative synthesis, but most importantly a wide and deep perspective that is not limited to the manic extremes. But architects keep following the money, instead of the value found in our expertise. Does every doctor consult result in surgery? Does every lawyer interview result in a lawsuit? Those professions get paid and take pride in the importance of knowing more. Architects should become the open, honest and willing experts in planning and construction, but avoid the insanities of the building boom mentality. That value will sustain in any economy, boom or bust. Duo Dickinson has been an architect for more than 30 years. His eighth book, A Home Called New England, will be released later this year. He is the architecture critic for the New Haven Register and writes on design and culture for the Hartford Courant. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Alto San Francisco House / CAW Arquitectos Posted: 17 May 2017 02:00 AM PDT  © Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh

© Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh From the architect. The Alto de San Francisco House corresponds to a weekend home, located in the hillside of The Andes mountain range near the Alto San Francisco valley, at a height of 1555 meters over the sea level.  © Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh The house is located in the south hillside of the Valley. From this point it's possible to obtain excellent views to the Mochoen Hill, the river and the San Francisco valley, as well as the summits of the Nevados 3 Puntas.  © Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh The weather condition was considered the starting point for the project. The strongly contrasted weather between summer (+34ºc) and winter (-10ºc) and the lack of natural light in the cold season due to the shadow produced by the hills and mountains that surround the valley.  © Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh One of the most important requests of the family was to make the most of the views down the hill, where the river and the valley can be appreciated at a close distance, and in a far view it's possible to appreciate the Chacabuco mountains and the Aconcagua valley to the south. In this way it was possible to propose a galzed facade to the south (views) and large windows in two levels to the north (light). The windows are designed to avoid the entrance of direct sunlight during summer but taking the most advantage of the natural light during winter.  Section A-A' Section A-A' Two pavilions are proposed according to the programatic layout of the spaces. The east pavilion contains the bedrooms, family room and the bathrooms. Bedrooms will take advantage of the double height of the windows to the north, using those as attics and viewpoints of the snowy summits. At the same time, natural lighting is allowed to generate solar radiation during winter. The west pavilion is proposed as a big space for the family to gather.  © Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh  Plan Plan  © Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh The two pavilions are connected by a northern corridor which contains the main access and also serves as eaves for bioclimatic control. The materiality corresponds entirely to pine wood MSD L=3.2m in diverse formats and sections.  Section detail 01 Section detail 01 The roofs are designed with a minimum slope, structured with trusses of high altitude that accumulate snow in winter, which is used as contribution to the thermal insulation. The snow is drained through open channels included in the eastern and western facades of the pavilions.  © Nico Saieh © Nico Saieh This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| 12 Libraries You Should Bookmark Right Now Posted: 17 May 2017 01:00 AM PDT

Like a reader hooked on a bestselling thriller, the design of libraries has enthralled architects and the general public for centuries. From the classical mahogany grandeur of the world-famous Long Room at Trinity College Dublin to the post-war, brick modernism of the British Library in London, the important role of libraries in our lives has historically demanded a degree of architectural thought and consideration. In recent times, however, that historic role has changed. With the digital age revolutionizing how we access, research, and communicate information, libraries are no longer reserved exclusively for books. Libraries today must act as ‘information hubs’, with the flexibility to accommodate a diverse range of media and arts. Architects have responded to the challenge of a new era, reimagining how libraries are built, experienced, and utilized, without entirely throwing away the rule book. Below, we have rounded-up 12 libraries from around the world, all with architecture from the top shelf. Public Library and Reading Park / Martín Lejarraga © David Frutos © David Frutos  © David Frutos © David Frutos Bibliothèque Alexis de Tocqueville / OMA + Barcode Architects © Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti © Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti  © Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti © Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti Joan Maragall Library / BCQ Arquitectura © Ariel Ramirez © Ariel Ramirez  © Ariel Ramirez © Ariel Ramirez The Pinch Library And Community Center / Olivier Ottevaere + John Lin.jpg?1494412902) Courtesy of: Olivier Ottevaere + John Lin Courtesy of: Olivier Ottevaere + John Lin  Courtesy of: Olivier Ottevaere + John Lin Courtesy of: Olivier Ottevaere + John Lin Media Library St Paul / Peripheriques Architects © Luc Boegly © Luc Boegly  © Luc Boegly © Luc Boegly Pavilion Library / SpaceTong (ArchiWorkshop) © June-Young Lim © June-Young Lim  © June-Young Lim © June-Young Lim Vasconcelos Library / Alberto Kalach Courtesy of: Alberto Kalach Courtesy of: Alberto Kalach  Courtesy of: Alberto Kalach Courtesy of: Alberto Kalach Story Pod / Atelier Kastelic Buffey © Bob Gundu © Bob Gundu  © Shai Gil © Shai Gil Constitución Public Library / Sebastian Irarrázaval © Felipe Díaz Contardo © Felipe Díaz Contardo  © Felipe Díaz Contardo © Felipe Díaz Contardo Montbau Library Rehabilitation / OliverasBoix Arquitectes © José Hevia © José Hevia  © José Hevia © José Hevia Library of Muyinga / BC Architects Courtesy of: BC architects Courtesy of: BC architects  Courtesy of: BC architects Courtesy of: BC architects Micro-Yuan’er / ZAO/standardarchitecture.jpg?1494413506) © Zhang Mingming © Zhang Mingming .jpg?1494413449) © Zhang Mingming © Zhang Mingming This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Forget Treehouses - Cliffhouses are the Future Posted: 16 May 2017 11:00 PM PDT  Nestinbox takes inspiration from birdhouses to provide an innovative solution to tackle housing crises. Image Courtesy of Manofactory Nestinbox takes inspiration from birdhouses to provide an innovative solution to tackle housing crises. Image Courtesy of Manofactory In major cities around the world, buildable land is at a premium. At the same time, a continued trend of urban migration has led to a shortage of houses, inspiring a wealth of innovative solutions from architects and designers. Swedish firm Manofactory have literally taken housing solutions to a new level, questioning why we need to build at ground level at all. Many animals, including birds, build their nests in trees, under roof tiles or in rock crevices above the ground. Humans already build simple nesting boxes for birds to live in, causing Manofactory to question why we can't build nesting boxes for ourselves – a simple house with several rooms, windows, and climate protection. Pointing to the numerous cliff walls in cities across northern Scandinavia and elsewhere, Manofactory have designed the Nestinbox – a small wooden house with a steel structure to be mounted on sheer cliff faces. .jpg?1494766952) The facade is clad in horizontal timber to reduce perceived building height. Image Courtesy of Manofactory The facade is clad in horizontal timber to reduce perceived building height. Image Courtesy of Manofactory As if defying gravity, Nestinbox hangs freely in the air with one side mounted against a cliff face. The design process began with the general blueprint of a birdhouse – a tall, light wooden structure with a simple sloping roof. This basic form has since evolved to develop a functional home for one or two users. The Nestinbox is clad with horizontal light and dark timber panels, creating a playful dialogue along the façade whilst contributing to a perceived visual reduction of building height.  An interior arranged around three floors provides compact yet functional living. Image Courtesy of Manofactory An interior arranged around three floors provides compact yet functional living. Image Courtesy of Manofactory  The floor plan provides 50sqm of open plan living, a double bedroom, and studio space. Image Courtesy of Manofactory The floor plan provides 50sqm of open plan living, a double bedroom, and studio space. Image Courtesy of Manofactory Inside, the house is arranged over three floors, with a living area of 50 square meters bringing it in line with space standards of major cities such as London. Each unit contains a kitchen and dining area, living room, WC with shower, a double bedroom, and a studio space lending itself to future use a children's bedroom. A central spiral staircase links all three floors, with a large void on the first floor creating a sense of space, cohesion, and openness despite the compact arrangement. The floorplan has also been considered to allow one side elevation to be free of windows, raising the possibility of mirrored Nestinboxes near or attached to each other without impeding outlook or natural light.  One elevation of the Nestinbox can be free of windows, allowing for combinations of several units. Image Courtesy of Manofactory One elevation of the Nestinbox can be free of windows, allowing for combinations of several units. Image Courtesy of Manofactory  A void an the intermediate floor creates a sense of cohesion. Image Courtesy of Manofactory A void an the intermediate floor creates a sense of cohesion. Image Courtesy of Manofactory Children have had treehouses for centuries – finally, adults have something cooler! News via: Manofactory.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 16 May 2017 10:00 PM PDT  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG

© Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG From the architect. GS1 Portugal is the Portuguese counterpart of the non-profit global body in charge of implementing the technological licensing origin identification systems of companies and products, promoting, among others, the renown barcodes, now designated qr codes.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG Its new headquarters, are the outcome of the 1st-prize in a competition held in 2014, in collaboration with artist Alexandre Farto aka Vhils. The building is located in the IAPMEI (Agency for Competitiveness and Innovation) Lisbon campus, in the Lumiar district. This campus, which is one of the first in Portugal specifically created for business innovation, is located on the surroundings of an 18th-century farmhouse on the boundaries of the city and was planned in the early 1970s based on an orthogonal grid largely inspired in the Anglo-Saxon university model.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG The new building makes use of the concrete structure of an existing 1980s office building which, in the meantime, became physically and technologically obsolete. The formerly called K3 building was a two-storey rectangular volume with a simple column grid holding a waffle slab system. In terms of programme, the building has three distinct areas, also corresponding to the different floors. The ground floor concentrates the public sphere of the centre’s activities, namely a showroom equipped with value-chain simulators and applied and interactive isles of multimedia information technology; it also includes a multi-purpose auditorium and technical areas. The second floor accommodates management and services in a fluid and informal open space, whereas meeting rooms, stationery and toilet areas are confined in opaque islands. Finally, the rooftop holds the social area with a bar/coffee shop opening onto a shaded terrace. Inside, the building is unified by two large circular voids cut-off from existing slabs visually enlarging the experience of space and user interconnectivity.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG  Diagrama Diagrama  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG In terms of finishing, the interior of the building intentionally plays on the idea of material reuse of the pre-existence. The rawness of the exposed concrete elements as well as the absence of false ceiling, thereby exposing all the electricity cable trays and AC ductwork, contrasts with the comfort and tactility of materials and finishes at users’ hands reach such as linoleum, cork, textiles and carpets.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG  Planta / Elevação Planta / Elevação  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG The facade zigzag system alternating between concrete panels and floor-to-ceiling glass panes, respectively facing North-South, reconfigures the relationship of the building’s views with the campus, while protecting the workspaces from excessive sunlight and yielding a luminous relationship with the garden.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG On the exterior, a part of the concrete panels has a bas-relief by VHILS, an art project on the outcome of a longstanding collaboration between the architects and the artist, namely on technology-based research for large scale precast concrete moulding. VHILS’ work and this project in particular, proposes a contemporary critic on the chaos of information and visual noise while questioning its disruptive role, which in turn is counterpoised by the presence of the human eye.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| You are subscribed to email updates from ArchDaily. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar