Arch Daily |

- House in Rua Faria Guimarães / Fala Atelier

- Red House / 31/44 Architects

- Kvåsfossen / Rever & Drage Architects

- Anti-Domino No. 02 – Wood Mountain / Daipu Architects

- Hangzhou Ya Gu Quan Shan Hotel / The Architectural Design and Research Institute of Zhejiang University

- MELLOWER Seongsu Flagship-Store / NBDC

- Open Call: Bauhaus Residence 2018

- Waikanae House / Herriot Melhuish O’Neill Architects

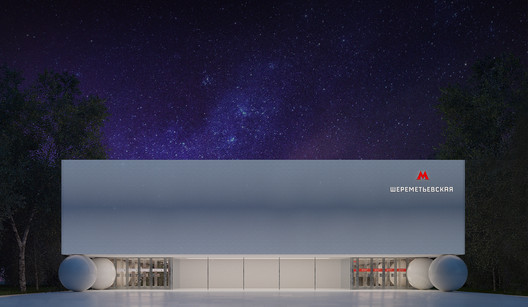

- AI-Architects' Competition-Winning Moscow Metro Station Design Utilizes "Friendly" Rounded Forms

- Ribeirão Preto House / SPBR Arquitetos + MMBB Arquitetos

- Paradise Gardens / Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands

- Renderings Revealed of Gehry Partners' Future Tree-Covered Playa Vista Office

- Santa Fe de Bogotá Foundation / El Equipo de Mazzanti

- Alejandro Aravena on Moving Architecture "From the Specificity of the Problem to the Ambiguity of the Question"

- Open Source House / studiolada architects

- Serious Question: Do Architects Learn Enough About Construction and Materials?

- How Earthbags and Glass Bottles Can 'Build' a Community

| House in Rua Faria Guimarães / Fala Atelier Posted: 20 Jul 2017 08:00 PM PDT  © Ricardo Loureiro © Ricardo Loureiro

Collage. Image Courtesy of Fala Atelier Collage. Image Courtesy of Fala Atelier  Collage. Image Courtesy of Fala Atelier Collage. Image Courtesy of Fala Atelier From the architect. The old house was found in a sequence of equally discrete buildings from different periods of the 20th century. Built originally for a single family, and abandoned for decades, the brief proposed transforming the ruin into a housing unit with five apartments, responding to the accelerated gentrification process in the area.  Before. Image Courtesy of Fala Atelier Before. Image Courtesy of Fala Atelier  © Ricardo Loureiro © Ricardo Loureiro The perimeter of thick granite walls was preserved and the interior structure was completely refurbished, recurring only to light wood elements. The fragmented arrangement of small inner rooms was replaced with a sequence of almost identically dimensioned apartments.  © Ricardo Loureiro © Ricardo Loureiro In every unit, a modular wall of openable plywood panels was painted in a deep blue tone, concealing different functions: kitchens, bathrooms, cabinetry. Only upon a second look it is understandable the distinction between the five units: the consistent system and visual relation between the several apartments finds its contradiction in the necessary adaptation of its rhetorical rigidity to the geometry of the staircase, the existing windows, the form of the roof. In each studio, a piece of natural stone with a different form unbalances the apparently symmetrical inner elevations.  Proposal plan Proposal plan The street facade acts as a theatrical device with its unorthodox use of the traditional local tiles. Two double-doors with different colours suggest distinct hierarchies.  © Ricardo Loureiro © Ricardo Loureiro This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 20 Jul 2017 07:00 PM PDT  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner

© Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner From the architect. Working with developer Arrant Land, 31/44 Architects has completed a new speculative development on an end-of-terrace plot in East Dulwich, south London.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner The location is a typical Victorian terrace ubiquitous in London's suburbs, but this newcomer is anything but pedestrian. The house shares the visual language of the pattern-book brick Victorian houses with their ornamental arched entrances, but it is designed in a contemporary idiom and confidently terminates the terrace with a highly distinct proposition.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner The ambition of this project has been to design a contemporary dwelling which references and evolves the character and rhythm of the terrace.  Section Section Red House takes its name from the warm red brick, which is evident as a highlight brick in the existing terrace and is used here as the main building material.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner The principal architectural move on the main elevation has been to appropriate the arched entranceway of the terrace into a large window onto a double-height hallway. The window is frameless, the arch is stripped of detail and the span is achieved with a pre-cast, pigmented concrete panel. The patterning in the panel is redolent of the decorative tiling found in the floor thresholds in the entrances of Victorian terraces.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner The site was formerly occupied by an end-of-terrace garage. The new house offers a blueprint for building on small, urban brownfield plots, as part of an emerging movement by independent developers to densify London through fine-grain, incremental development.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner The plan is cleverly designed to fit a spacious three-bedroom house with flexible reception spaces onto a tight brownfield plot, without compromising privacy for the occupants or neighbours.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner On entering the house into a double-height atrium, a short flight of steps descends to ground level, where the plan opens out to a kitchen/diner and two reception spaces. A central glazed courtyard and rear courtyard bring natural light and the outdoors deep interspersed with pockets of sunlight and greenery, which can be enjoyed in all seasons. The open plan living spaces are unified with a black concrete floor and animated by a wood burning stove housed within the exposed concrete plinth of the chimney, whose red brick stack rises up beyond the roofline, tethered to the house by concrete supports.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner A dramatic oak staircase top-lit by the front window leads up to the two bedrooms and bathroom on the first floor, and master bedroom with en-suite shower room at the top.  © Rory Gardiner © Rory Gardiner This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Kvåsfossen / Rever & Drage Architects Posted: 20 Jul 2017 05:00 PM PDT  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger

© Tom Auger © Tom Auger From the architect. In 2014 a salmon ladder was opened at the Kvåsfossen waterfall in Lyngdal, Norway. As part of the ladder, an underground artificial pool was included to allow the public to see the passing salmon. Due to the public interest and for practical reasons, a visitor centre was built to accomodate the public here.  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger The plot just above the salmon ladder provides a spectacular location at the edge of a cliff with the Lynga river at the bottom. As such, the location itself and the visitors´ centre provide a striking contrast between being at the edge of the cliff, as opposed to down below in the underground salmon ladder. In addition the centre is surrounded by dense oak woodland, which adds to the distinctive character of the location.  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger A part of the experience is to walk the path along the river up to the waterfall, cross an old bridge and pass through woodland back to the visitors centre. With the main road nearby, the building also needs to provide a screen, such that the landscape can be enjoyed without being disturbed by noise from traffic. This in addition to the fact that the building is visible from the road and provides a signal that here there is something of interest. This dual role is provided by the roof, which due to the buildings low position in relation to the road, acts as a facade towards the road.  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger  Plan Plan  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger The roof is both large and low and has some typical and some unusual characteristics. The sloping roof atop the rectangular plan is in itself typical 70´s style (and thereby related to many of the houses in the nearby village), whilst the juxtaposition of the two roofs, together with the lack of eaves and the roofing material are not. The ventilation units on the roof have a double function as signs, and they also contribute to a subtle effect of being atypical, since they are too large and of the wrong type material to be chimneys or louvers.  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger From the subdued aspect towards the parking lot, the building opens up internally and is much larger than the first impression from the entrance area. The apparent limited size viewed from the east gives the impression of a residential building, whilst the actual size is much closer to a public building. A third ambiguity lies in the choice of materials and colours. The external cladding is impregnated with traditional tarbased stain. The smell of this gives the impression of 150 year old building traditions, but at the same time the colour gives a much more modern appearance.  South Elevation South Elevation  East elevation East elevation  North Elevation North Elevation Up in the visitor´s centre a natural favourite with the public is the area in the centre of the building, where you can sit by the window apparently on the edge of a dramatic cliff edge. This has a lot in common with Jensen & Skodvins "Juvet Landskapshotell" at another location in Norway (Valldal, Møre og Romsdal) and represents a further development of the close-to-nature effect applied there, whereby in this case the floor is sunk immediately in front of the window to provide a sitting place.  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger The different windows in the building provide varied views of the river as one moves along the cliff edge. The views towards the dense oak woodland outside give a varied light effect that is best experienced by moving a small distance away from the windows. Some of the light openings are formed as plain glass panes and present "removal of wall areas", whilst others have defined frames and present "holes in the wall". The latter are similar to traditional windows and contribute to the ambiguity between the traditional and the modern, which also interacts in the building´s exterior.  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger This building is both small and large. It is both modern and traditional and it represents both comfortable places for contemplation up on the cliff's edge, and raw encounters with the dripping wet infrastructure of the fish ladder underneath it.  © Tom Auger © Tom Auger This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Anti-Domino No. 02 – Wood Mountain / Daipu Architects Posted: 20 Jul 2017 03:00 PM PDT  Courtesy of Daipu Architects Courtesy of Daipu Architects

.jpg?1500492101) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo From the architect. In recent years, our studio has been working on a series of renovation projects. This is a legacy phenomenon caused by the mass and fast production during the past 10-20 years in the construction industry, and it impels usto proactively reflect on and respond to the professional reality behind this phenomenon. .jpg?1500492142) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo All of these renovation projects can be seen as simple replications of the Domino system in the horizontal dimension and repeated compositionsof such system in the vertical dimension. A word, a sentence, or even a piece of manifesto, does not become proper or rational even if it has been repeated thousands of times. That is why we make different attempts in each renovation project to respond to these existing and constantly repeated "errors" and "lack of quality", experiment with more enriched and more prototype-drivensolutions to renew the existing structure, and expect to generate completely new building systems and structural systems. .jpg?1500492172) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo We call this series of renovation projects as "Anti-Domino". The Anti-domino No. 02 Project being presented is the first completed one from this series.  Diagram Diagram How to create a response to integrate the outdoor environment (including the distant view of Yangtze River) with such a concrete structure within only two column spans and less than 100 square meters? This is the primary question we consider. It also includes the reason why the owner chooses this site for his pub, ----he wants to have all the people who like beer in Chongqing come here to enjoy the pleasing environment, as well as the nice and unique skyline of the Yuzhong peninsula from both indoor and outdoor perspectives. .jpg?1500492152) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo .jpg?1500492162) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo People who arrive in Chongqing for the first time will feel excited when they see such distinctive geospatial features. However, it is regrettable to see all the new buildings in this city (including commercial, residential, urban complexes etc.) are the same type as the buildings in all other Chinese first-tier cities. The architectural forms do not respond to and respect the local topography, landscape and climate. .jpg?1500492187) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo So we employ a set of new structural language in this project, to simulate the special mountainous space of Chongqing. The mountainous terrain is introduced into the restricted concrete space with integration of a more subtle scale of furniture. This amplifies the dimensional feeling of the space, and also introduces the more relaxed body gestures (sit, lie, squat, lean) of the Chongqing local people (as well as how a natural person in an old neighbourhood will behave) into such a scene of modern life.  Diagram Diagram This set of design can be seen as topography, landscape, or furniture design. It includes the guide of sight line at the entrance, spatial partitions, footrests of bar counter, small articles for stroking while drinking, and large wood sofa and so on. The whole model is made of pure solid wood and carved by computerized digital control machine. The model is designed on computer, then prefabricated in the factory and assembled on site, which this technique improves the completeness of the model and also saves the time of on-site work. .jpg?1500492121) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo The solid wood will partly expand or contract with the effect of the local wet weather, and varied wood grains will emerge on the surface. We expect it will dehisce after one or two years and show a more natural effect of wood piling, just like the appealing scene in a warehouse of timber mill. People will also leave the signs of frequent use on the surface, which seems to implicitly suggest the changes of fermented beer in the barrel. .jpg?1500492132) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo This project also provides a chance for us to rethink the megastructure such as super high-rise. As a critical reflection toward the Domino system, we find that the existing super high-rise design is only a repeated stack of the single layer structure, allowing limited connection between the layers. Moreover, the super high-rise is not only a closed structure inside, but aslo a lonely island in the city. It is like Narcissis, who only has self-worship, and refuses the possibility of any interaction.  Diagram Diagram So we use such a new topographical structure to replace the previous horizontal floor, and a completely new public space will be generated inside the super high-rise. It creates connection through the roof garden, top-level residential blocks, work units on the middle floors, and the commercial space on the ground floor. The efficiency of high-rise co-exists with the comfort of lower level, and landmark and openness reach a settlement. Such a picture, a real democratization of landmark-brimming era. .jpg?1500492111) © Qingshan Woo © Qingshan Woo This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 20 Jul 2017 01:00 PM PDT  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang

© Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang From the architect. The base is located at the southwest corner of the intersection of San Tai Shan Road and Hu Pao Road of West Lake District in Hangzhou. There are some hills surrounded with wide viewing; the landscape is beautiful inside and the natural vegetation well preserved.  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang The hotel's total building area are of 31363 square meters, the total number of rooms are 182 rooms, from which the main parts of hotel are 109 rooms, the main type of single room are 21 building and 73 rooms with banquet hall, Chinese restaurant, Japanese restaurant, conference room, gym, indoor swimming pool and other facilities.  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang The design is adhered to the purpose of "respecting the natural environment and inheriting the historical heritage", through the construction of the ground architecture; the connection and symbiosis between nature and humanity are realized.  Zone A First Floor Plan Zone A First Floor Plan The backyard of entrance landscape is located in second floor, which used the minimal design techniques so as to show "white when black" representing the general artistic effect. Through the background of the north white wall, there are row of tall cedar retained in the base, when you observe from the entrance ramp or entrance porch, the ink image of white walls, green trees and natural rocks is reflected in the calm water, which present the outline of entrance space and express the quietness and Buddhist mood.  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang The main functions of the hotel community are composed by courtyards located on both sides of the central axis of the main entrance. There are some tall arbors at the eastern side of the courtyard in the base. The west side courtyard is built on the top of a roof so as to create a private atmosphere of two rooms with a simple atmosphere.  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang  Section 2-2 Section 2-2  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang The hotel rooms are located at the southwest of the main part of hotel, which is surrounded by the green courtyard and spotted by green plants and dry stone, and there are several pieces of trees, shrubs, and a ancient Pavilion at the corner, which makes the courtyard prosperous and having rich sense of place.  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang The standing room area are located on the west side of base, which is designed by changing of courtyard, vertical relationship of local conditions and different degree of openness and consistency, so the building volume is cut organically and transforming its space.  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang White walls, black tiles, deep eaves; the slate floors are simple and delicate; the roofing color is black grey tile roof; and the achievement of precious warm tone, which is formed by the carefully chosen pineapple wood wall panels of the building groups presenting the white wall and forming the background of China fir forest, building a systematic and full of connotations design language, making the hotel in the rich southern charm tone, clearly expressing the clear characteristics and the artistic conception of building form of Hangzhou style with the poetic invisible sense.  © Zhao Qiang © Zhao Qiang This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| MELLOWER Seongsu Flagship-Store / NBDC Posted: 20 Jul 2017 12:00 PM PDT  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo

© In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo 'No past No future' ' Brooklyn ' in the United States , ' Hackney 'in the United Kingdom and ' Seong-su ' in the Korea, which successfully led the rebuilding of the urban regeneration strategy through the preservation of the past.  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo Since 2010, 'Seong-su' has been designated as the " City of Urban Renaissance Project " in 2014. Reflecting the development of urban regeneration, which is not a general development, we agreed on the idea of reviving social and cultural functions through design, cultural and ecological environment, and the restoration of the urban economy.  Concept Concept Mellower also wanted to include their own specificity of the coffee and bakery in the first place, not to stay in the traditional Asian brand image. Instead of breaking all of the old ones and creating new ones, we created new identities and designs in existing architectures and spaces, satisfying the needs of these clients and regions.  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo - Concept 'Rejuvenation' The concept of this project is Rejuvenation. It means being young again and recovering. In the light faded place can regain momentum again through penetrating novelty.  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo - Design We wanted to show the design concepts through the look of this architecture's exterior. And leave the frame of the building untouched, which was formerly a dyeing factory, inserted two creative boxes connecting the top and bottom of the building to create a new feeling. The white boxes is to liaise between external and internal place and contain the main features of the brand.  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo On the first box, the main function of the brand was extended from the downstairs to the upstairs by placing the coffee Bar and the roasting Room on the 1st floor and academy and office on the 2nd floor. Another independent box was placed in the bakery kitchen.  1st Floor Plan 1st Floor Plan  2nd Floor Plan 2nd Floor Plan And the stairs connected two boxes showed the lively area by covering rainbow.  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo - Think Existing buildings used external concepts to provide customers with free service.  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo And as the first flagship store of the Mellower was established in Seoul, we planed to place the creative boxes to make room for employees to build and spread their skills  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo - End Hopefully, Mellower is ripe for new time to mature in the space that coexisting with the past and present.  © In-Woo Yeo © In-Woo Yeo This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Open Call: Bauhaus Residence 2018 Posted: 20 Jul 2017 11:00 AM PDT  Living and working in the Schlemmer House in Dessau In the 1920's the Masters' Houses in Dessau became the epitome of an artist community of the twentieth century. This is where Walter Gropius, Oskar Schlemmer, Georg Muche, László Moholy-Nagy, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee and their families lived next door to each other. Here they were joined by their friends and visitors. Artist collectives, artist couples and artist friendships developed here, with everyone working together in the open structure of the model homes located in a park. However, when the Bauhauslers left in 1933 the area became deserted and the work created as a result of the artistic effort was abandoned. Since February 2016 the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation is enabling young international artists to once again live and work in the Schlemmer house – even if the restrictions of the perseveration of cultural heritage attached to the status of a UNESCO World Heritage Site are very strict. With the new format the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation would like to promote the current focus of attention on the Bauhaus heritage, revitalise the Masters' Houses and in this context promote artistic and creative work of international significance which will then at the end of the residency period be displayed in the Gropius House until the Bauhaus anniversary in 2019. Participation conditionsThe programme is catering to artists with an overall interest in all those areas that are historically being represented by Bauhaus and that have developed from it until today: painting, design, textile, architecture, sculpture, photography, film. Please appreciate the fact that the Open Call is not open to students. Teams are welcome. Application (German or English): We require the following information from you:

Applications in paper or other formats will not be accepted and will therefore disqualify the applicant. ! ! ! Closing date for applications ! ! ! Announcement of the winnersIn the autumn of 2017 two artists will be selected for the year 2018 by a jury. The winners will be announced through a press release at the end of October 2017. JuryThe jury consists of Dr Claudia Perren, director of the Bauhaus Dessau The Foundation's performancesThe Bauhaus Dessau Foundation will provide the selected artists with the

The artists' obligations

With the assistance of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, the artists are free to apply for additional external funding for their stay. Artists-in-Residence time periodThe three-monthly Artist-in-Residence stays will take place between April and October 2018 in consultation with the Foundation. You are expected to be present in Dessau. Learn more about this opportunity, here.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Waikanae House / Herriot Melhuish O’Neill Architects Posted: 20 Jul 2017 10:00 AM PDT  © Andy Spain © Andy Spain

© Andy Spain © Andy Spain From the architect. Simplicity is deceptively complex at Herriot Melhuish O'Neill Architects' (HMOA) Waikanae House which won a housing award at the 2017 NZIA Wellington Architecture Awards. The NZIA judging panel observed that the simple external forms of the structure contain a hidden complexity within. "Viewed on approach this house appears to be a simple composition of box forms. However, on entering and circulating through it, the composition reveals surprises, subtle complexities and a deft handling that responds to the site and the client needs."  Ground Level Plan Ground Level Plan Now a finalist in the 2017 NZIA New Zealand Architecture Awards, the Waikanae House was designed by HMOA director Max Herriot and architect Oliver Markham. The architects' careful design and sensitive landscaping means this elevated beachfront holiday home sits comfortably in its seaside environment while still capturing panoramic sea views towards Kapiti Island and framed vistas of the Tararua Ranges.  © Andy Spain © Andy Spain The judges said: "From the seaward side it sits horizontally in clever contrast to the verticality of the landward view. In a sense, it inverts the form of Kapiti Island to which it faces. Cuts through the form, glazed and open, capture landward and seaward views. The Waikanae house presents, both simply and complexly, a very well-composed and compelling architectural outcome."  © Andy Spain © Andy Spain The home is made up of a main house with two bedrooms, a bathroom, living areas and a roof top lounge and deck, plus a separate two-bedroom guest wing on top of the garage.  © Andy Spain © Andy Spain The design of the house comprises macrocarpa timber 'volumes' to create sheltered spaces for living and entertaining. The deeply overhanging roof planes provide respite from the summer sun. An outdoor swimming pool is nestled among the dunes to escape the prevailing coastal wind.  © Andy Spain © Andy Spain This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| AI-Architects' Competition-Winning Moscow Metro Station Design Utilizes "Friendly" Rounded Forms Posted: 20 Jul 2017 08:30 AM PDT  Courtesy of AI-architects Courtesy of AI-architects Russian architecture firm AI-Architects has been selected as the winners of a competition to design the new Sheremetyevskaya Metro Station in Moscow, Russia. The open international competition sought proposals for three stations to be located along the capital's new metro line: "Rzhevskaya," "Sheremetyevskaya," and "Stromynka." The other two winning firms included Blank Architects for the "Rzhevskaya" station and Map Architects for the "Stromynka" station.  Courtesy of AI-architects Courtesy of AI-architects AI-Architects' scheme draws from the materiality of "Russian aristocratic traditions" and employs a series of rounded forms, which the architects refer to as "friendly" and capable of filtering large flows of people to and from the station platform. The design of the Sheremeryevskaya station combines the grandeur of Moscow's historic stations with the ergonomics, functionality and practicality of the city's more modern stations, resulting in a project that the architects describe as both "elegant and technological."  Courtesy of AI-architects Courtesy of AI-architects  Courtesy of AI-architects Courtesy of AI-architects Named for the Russian nobleman Count Sheremetyev, the station will feature porcelain sets and tiles, a material common to the architecture of Russian nobility. Above ground, spherical glass pedestals support the 70-meter-long station roof, giving it the appearance of floating. This language is continued to the underground, where rounded pylons feature a granite finish meant to resemble cracked porcelain pieces.  Courtesy of AI-architects Courtesy of AI-architects Several design choices inside the station help to improve the user experience, including benches integrated into interior walls and mirrored surfaces intended to reduce the speed of passengers, who will involuntarily slow down to look at their reflection.  Courtesy of AI-architects Courtesy of AI-architects  Courtesy of AI-architects Courtesy of AI-architects This is the second significant commission for AI-architects in Russia's capital city, following the completion of the redesign of Borovotskaya Square in the historical center of Moscow by the walls of the Kremlin. Construction on the Sheremeryevskaya station is estimated to be completed in 2020. News via AI-architects.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Ribeirão Preto House / SPBR Arquitetos + MMBB Arquitetos Posted: 20 Jul 2017 08:00 AM PDT  © Nelson Kon © Nelson Kon

© Nelson Kon © Nelson Kon From the architect. This house is structured on four pillars of direct foundation on the bedrock at one and a half meters deep. A pair of beams, inverted on the ceiling, structures the roofing slab and anchored the floor slab, without beams.  © Nelson Kon © Nelson Kon  Model Model  © Nelson Kon © Nelson Kon The topography of the site had been decharacterized. On the pretext of this is that it was decided to move the existing ground volume in the batch to organize three garden terraces on different level of quotas, as if they were three stones, and a walk between them at street level.  © Nelson Kon © Nelson Kon  Section Section  © Nelson Kon © Nelson Kon The street garden (level 2.00) extends the upper room incorporating the front setback, usually lost behind a wall. The bedroom garden (level 1.80) shades the north face and provides a more sheltered outdoor area as an extension of the rest environments. The courtyard garden (level 1.20), in the mid-level, makes smooth passage between the two floors and enjoys the small vertical distances achieved by the structural solution.  © Nelson Kon © Nelson Kon This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Paradise Gardens / Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands Posted: 20 Jul 2017 06:00 AM PDT  © Nick Gutteridge © Nick Gutteridge

© Paul Riddle © Paul Riddle From the architect. This development of six houses occupies a former derelict yard in the heart of the Ravenscourt and Starch Green Conservation Area, next to Ravenscourt Park. The scheme had to resolve a tight site, overlooked by neighboring properties and next to a locally listed terrace. The solution is a contemporary response to the local vernacular, with five three-storey houses forming a terrace that steps forward incrementally along its length. A sixth, two-storey, house is built within the walls of Latymer House, which once stood on the site.  Ground Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan The houses are entered from a cobbled courtyard, which provides six parking spaces and cycle storage for up to 12 bikes. This leads to a lush landscape of private and communal gardens beyond the dwellings, designed by eminent landscape designers Bradley-Hole Schoenaich, creating a beautiful setting for both the surrounding properties and the development itself.  © Nick Gutteridge © Nick Gutteridge  Sections Sections  © Nick Gutteridge © Nick Gutteridge The terrace is detailed in buff-coloured brick with shallow-pitched zinc roofs and aluminium-framed windows. The dark zinc dresses down the western gable wall and the entrance porches. The sixth house is built from a darker brick to match the retained walls. .jpg?1500480837) © Nick Gutteridge © Nick Gutteridge Spatially generous, with light-filled interiors, the houses are designed to be flexible in layout. A steel frame structure gives the flexibility to break through laterally, and there are no load-bearing elements between party walls, which allows for future change. Unusually, the houses were designed for the private rental market, which demands an appropriate robustness and the ability to be redecorated easily.  © Paul Riddle © Paul Riddle The buildings go beyond Code for Sustainable Homes (CfSH) level 4 through the upgrade of façade performance in line with Code 5 requirements. Excellent air tightness levels and thermal performance are achieved through the careful consideration of thermal bridging and solar gain, the use of heavily insulated wall and roof construction, and triple glazing. Each house includes a highly efficient mechanical ventilation and heat recovery system and boiler. High levels of acoustic performance have been maintained and the lighting design seeks to maximize the use of natural daylighting minimizing the need for artificial lighting. The land prior to development was of inherently low ecological value – it has been greatly enhanced through careful consideration and inclusion of large areas of private and shared soft landscaping, as well as bird and bat boxes that are incorporated into the façades. Rainwater is collected and used for external automated irrigation of the landscaped areas. This development has been given a RIBA National Award 2017 and a Housing Design Award  © Paul Riddle © Paul Riddle This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Renderings Revealed of Gehry Partners' Future Tree-Covered Playa Vista Office Posted: 20 Jul 2017 05:30 AM PDT .jpg?1500566908) via LA Department of City Planning via LA Department of City Planning Renderings for a new office building in the Playa Vista neighborhood of Los Angeles designed by Gehry Partners have been revealed in documents released by the LA Department of City Planning. Called New Beatrice West, the eight-story development consists of a series of terraced glass boxes, capped with abundant vegetation aimed at contributing passive energy-efficiency to the complex. The new building will integrate an existing adjacent office building that currently houses the offices of Gehry Partners. .jpg?1500566871) via LA Department of City Planning via LA Department of City Planning Located on a site at the corner of Jandy Place and Beatrice Street, the building would consist of five floors of office space above three floors of public space containing restaurants and retail stores. Two levels of underground parking will join three levels of above ground spaces, allowing the complex to accommodate up to 845 vehicles, while long- and short-term bike parking spaces, locker rooms and showers will encourage employees to use a more environmentally sustainable means of commuting. .jpg?1500566881) via LA Department of City Planning via LA Department of City Planning .jpg?1500566918) via LA Department of City Planning via LA Department of City Planning The building will employ sustainable strategies throughout, including low-flow water fixtures and energy-efficient lighting. During the day, a majority of spaces will be able to be naturally lit. New courtyards, pathways and landscaping will be added to the site, contributing to the overall aesthetic of green walls and roofs. Early estimates indicate construction will take approximately 22 months. News via Curbed, LA Department of Planning. .jpg?1500566892) via LA Department of City Planning via LA Department of City Planning This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Santa Fe de Bogotá Foundation / El Equipo de Mazzanti Posted: 20 Jul 2017 04:00 AM PDT  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango

© Andrés Valbuena © Andrés Valbuena From the architect. A connecting building - a healing space The project´s main idea: the connection. There are different connection levels that our proposal will solve: Urban connector  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango  Location Location  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango We designed dos big open spaces at the edges of the two avenues, both with a lot of vegetation, green areas, commercial stores, coffee shops and a multipurpose auditorium that will create a relationship between pedestrians and the area. Open spaces, even if they are separated from the existing hospital, they will look connected at the pedestrian level by the main lobby of the building, as well as generating new flows and activities, turning the building into an urban bridge. We state a complete urban solution that will make the University Hospital as a reference and meeting point in its environment.  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango Connecting the existent  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango The actual hospital is the result of an addition of architectonical pieces that answer to programmatic needs, technological and scientific advances. In consequence this has created a maze of buildings and flows.  Section 01 Section 01 Our proposal tries to retake the initial idea of a complex. The idea of the connector building recovers the proposal of the axe between the existing and the new buildings. It wants to take aside the idea of joining buildings and punctual expansions and understand the hospital as a totality. This will generate necessary connections for the correct operation of the different levels, avoiding the uncontrolled growing of small pieces without relation. We propose a building with a core that will reorganize the actual vertical and horizontal flows as well as working as a linking element between the new and the existent.  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango Therefore we want to rescue the intention of the patio and natural lighting in each of the spaces, an element of vital meaning in the healing process.  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango Connector of the new  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango The tower for ICU is stated as the next operational heart of the hospital and the surgery service. Connected by bridges and an exclusive elevator for patients.  Axonometric Axonometric Existent coherence  © Andrés Valbuena © Andrés Valbuena The building´s image is an important element for the iconic design. Through its materiality and configuration, the façade leaves its condition of only working as a skin and turns to be an element of meanings and functions; it turns to be an element of identity for the foundation, configuring an integral element of the whole campus. We will use a brick façade that will allow the proper integration to the actual language of the hospital, raising the idea of sobriety in the architectonical design. On the other hand, the facades innovation in which the brick would not be used as a structural element but as an aesthetical one. The mudejar configuration will generate particular ambiences inside of the building. The disposition of the bricks will let natural light come in different levels and intensities. This façade allows the use of the brick wall as a membrane that helps to have a semi-private relation with the exterior. The relation with the outside increases when having windows from bottom to top, the highs of the windows change because the person who spends more time in the room is a lay down patient and needs to have a view from the bed. The patients have the possibility to look to the city, the mountains and the sky. On the back of the brick skin, there is a glazed skin to prevent pollution, contamination, noise and weather isolation for a really temperature and sound control.  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango  Facade Detail Facade Detail  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango A healing space  © Andrés Valbuena © Andrés Valbuena It is the patient who gives sense to the hospital and he has to be in the first place always. In second place it is the staff that requires adequate ambiences to do their work with the best attitude. A third group is the population that goes to the building for different reasons. Our conceptual proposal is to do a high, singular and emblematic building. We understand the foundation need as an architectonical idea and not a conventional hospital.  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango The volumes configuration in two autonomous buildings has the characteristic of opening new luminous spaces, comfort not only functional but as spatial quality and generosity; friendly environments.  © Alejandro Arango © Alejandro Arango The hospital needs to be transforming and adapting continuously, a dialogue between offer of aid, physical resources, technology, process, functionality.  9th floor plan 9th floor plan We propose in the 9th floor a new place that is totally different from the traditional; having a solarium full of plants in the middle of a hospital may sound a total mistake, but it increases health in patients that they not feel trapped in a hospital. The hospital design overall is made for accelerating healing process, light, views and nature help in the mind recovery after a surgery or a long stay in ICU.  © Andrés Valbuena © Andrés Valbuena HOSPITAL PRINCIPLES  Model 01. Image Courtesy of El Equipo de Mazzanti Model 01. Image Courtesy of El Equipo de Mazzanti  Model 02. Image Courtesy of El Equipo de Mazzanti Model 02. Image Courtesy of El Equipo de Mazzanti - Safety: precise control when we have really delimited the private areas from the public ones.  © Andrés Valbuena © Andrés Valbuena - Innovation: solutions for the latest technology in terms of equipment, procedures, etc.  © Andrés Valbuena © Andrés Valbuena This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 20 Jul 2017 02:30 AM PDT  © Álvaro González © Álvaro González This interview with the winner of the 2016 Pritzker Prize, Alejandro Aravena, was published last year in Issue 31 of Revista AOA, a Spanish-language magazine published by the Association of Architecture Offices of Chile. The interview was conducted by the editorial committee of Revista AOA—represented by Yves Besançon, Francisca Pulido and Tomás Swett—and is accompanied by photographs by Álvaro González. Aravena's openness and warmth allowed them to deliver a profound questionnaire about his thoughts and architectural projections, especially in light of Aravena's Venice Biennale which took place last year. Without a doubt, 2016 marked a period of international consolidation among architects, which in January led to the first Chilean winner of the Pritzker Prize and also the first Latin-American director of the Venice Biennale of Architecture. From there, as the title of exhibition says, he continues "reporting from the front" and invites architects all over the world to share the battles that they face in their countries. In total, there are 88 works from 37 countries—among them four projects from Chile—that address themes related to segregation, inequality, suburbia, sanitation, natural disasters, housing shortages, migration, traffic, trash, pollution, and community participation. Along with the declaration of principles that accompany the call that defines the Biennale, Aravena has explained that the exhibition this year is "about the knowledge and the approach to architecture that through intelligence, intuition, or both, is capable of escaping the status quo... And in place of resignation or bitterness proposes and does something." In reality, that is what defines the work of Aravena and of Elemental, who in a step beyond "doing something" released the use of four of their designs for social housing. Any architect or public or private institution can now utilize the plans and construction details of Quinta Monroy in Iquique, Colonia Lo Barnechea in Santiago, Villa Verde in Constitución, and the award-winning housing of Monterrey in Mexico. It is a decision that speaks of "the necessity to work together to approach the challenge of rapid urbanization around the world," much in line with the theme of the Biennale. In a long conversation with the editorial committee of Revista AOA—represented by Yves Besançon, Francisca Pulido and Tomás Swett—those themes were addressed, taking as a starting point what is being done—or rather failing to be done—to make architects capable of defining appropriate questions that permit architecture to give the necessary social response.  © Álvaro González © Álvaro González You often refer to the necessity of finding the questions before giving the answers to an architectural problem. With that in mind, what do you think about the training of new architects? What is needed to define the true problems of possibility and from there to approach architectural education? If you clarify what architecture should be, what comes next is what or how it should be taught, so I will try to tackle the issue from various directions. First, we assume that what we teach today is basically a set of disciplinary rules by which the objects produced are then judged. In general, this alludes more to artistic form and compositional rules than a specific disciplinary tradition. While that can develop and lead to the expansion of one's own internal set of rules, the risk is that many of the rules and the types of problems are not relevant to the rest of society and only matter to other architects. So the architectural discussion becomes a specialized critique or a formal stylistic analysis that the rest of society doesn't care about. For this reason, the first question is how to introduce a person to this body of specific knowledge and how to start from entirely non-specific problems that are important to them, and on which any citizen can have an opinion. That is to say, to move from the specificity of the problem to the ambiguity of the question. If you are able to understand that the problems that architecture can deal with are those which are important to society, the way to contribute is from that body of specific knowledge. That is, to translate the forces into playing with form, which is what architects know how to do. The idea is not to become an economist, politician, or anthropologist, but knowing their languages allows us to understand the code of forces that must then be translated into form. In general, we do little exercise in understanding the languages of other disciplines and in doing so we abandon the core of architecture, which is making projects. A few years ago, in a discussion I had with Hashim Sarkis, then at Harvard and now director of MIT, we said there was a moment in which architecture bifurcated, probably at the end of the 60s or the beginning of the 70s. On one side were those who claimed a kind of creative jurisdiction to be geniuses, and they developed all the possible "isms": postmodernism, minimalism, deconstructivism, etc. But this disciplinary autonomy has a very thin line with irrelevance, that is to say, to be occupied with things that no one cares about but the architects themselves. The other side is those who opted to focus on problems of poverty, underdevelopment, and inequality, but abandoned the specific knowledge of the architect to become a consultant of organizations with acronyms and paperwork. Seen this way we can conclude that the problem is in not organizing the information in the proposed key. The value of architecture is that it does not take the information to make a diagnosis, but a proposal. The organization of the "particles" of information in the proposed key is the specific power of the architect. Assembling the puzzle more than organizing loose pieces? It's like tempering a sword. When it is achieved it is because all the particles are in the same direction. They do not necessarily all agree or say the same thing, but they point in a direction. The challenge of architecture, and by extension of its teaching, is to be capable of departing from outside of architecture, in that environment of ambiguous problems that matter to society, and synthesizing the key of the specific architectural proposal, so that the proposal is then returned to society and judged. For this reason it is very difficult to produce a good work of architecture. What, then, would you define as good work? It is something capable of synthesizing a spectrum or layers of variables that set out from absolutely practical and concrete issues. The "star architect" is criticized for a preoccupation with the iconic dimension of architecture, responding to a strict discipline when they also need to worry about the problems of the people. But if you consider only the problems and abandon the artistic dimension of the project, it is equally incomplete. Returning to the theme of education, we should understand that if architecture has a power, it is synthesis, and in this sense we do not have to be afraid to start by designing the question and identifying the variables of the equation. When you speak of "equation" what you spell out are the terms to which you will need to respond later. The difficulty—or also the grace—of architecture is that for any particular equation there is not a single answer. But the ability to make explicit what is informing the shape of the project is the type of issue one would expect to address when teaching architecture. Normally what we do as architects, and what we are taught to do, is that given the possibility that contradictory forces influencing the final work or object will not all be neatly judged by the architectural set of rules, you can ask the question.  © Álvaro González © Álvaro González How to make the sketch after finishing the project... Exactly, and this has many difficulties. On one side, as an architect one should be capable of synthesizing the key to the project and in a single proposal include contradictory forces. On the other side it requires a paradigm shift: if we keep asking you for a social housing project that only responds in the sculptural dimension, we are misjudging. It is the question that should be distinct, not the answer. For this reason I am quite critical of the teaching of architecture today, because in general what I see in academia is a circuit of people who depend on publications, symposiums, and conferences, and who usually focus only on themes that sound very powerful. The problems that are actually important do not seem to have merit from the academic point of view, they are very common and current and that has no glamor. It is necessary to understand and give more stress to the questions and then, when judged, understand as well the real complexity of the problem, and ultimately we should reevaluate the way in which we decide if a project is or is not successful. Forces at PlayThe capacity to question that a student or young professional has today is usually low, looking for immediate and direct results. The initial stage of questioning is quite limited, the logic of the process of design does not seem to be developed in the formation of architects. Prior to questioning is the openness to approach the problem with everything that comes to the case, a prejudice that allows one to distinguish the relevant from the irrelevant. It is not questioning in the critical sense or negative judgment. But it is complex, because when a client comes with a project it will not necessarily have a clear question. Constructing the question is part of the creative process, one should discriminate between what is important and what is not: what will inform the form, the structure, the budget, the climate, the regulations, the user, etc., starting from very concrete and measurable questions. However, there are intangible dimensions, governed by what we call "ineffable certainties," where it is difficult to know if they are good or bad but which also form part of the project, like the character of a building. That's where the difficulty lies in architectural production. As much as you have identified and created a hierarchy for all of the variables, there is no recipe for constructing the question, it is a creative act. And then the jump from identifying the variables of the problem to the answer that synthesizes all of the forces at play... It is an art, in the sense that it moves with partial certainties, it is intuitive, it is not a guarantee, nor is it a linear process ensuing from the circumstances, variables appear that are more than the circumstances and yet they are relevant... To teach all of that is very complex.  © Álvaro González © Álvaro González Does any subject generate a possible line of questioning to ask "the" question? Which themes should always be addressed within the equation? In principle, I would say that it is enough if there is agreement on something that matters. One of the ways of seeing if you approached a problem well is that you don't need to have a seminar to explain it. That is to say, "pollution," which we all understand to be a problem, we all experience it and we all can have an opinion. The same with congestion, segregation, insecurity, sustainability, immigration... The issue is how to enter a discussion that does not pertain to architecture but with the specific knowledge of architecture, that is to translate a form and then organize in a proposal what you managed to elevate for that problem. It has physical components, process components, governance components which break down into their social components, political, economic, environmental, etc. The point is that it is something that everyone understands, that is desirable to engage with, and then that the input to the problem is creative. What makes the difference is not just hard work, because if you are not able to bring something that illuminates and elevates the problem to a different state, that effort counts for nothing. Nor does it matter to just have an idea and then not be capable of implementing or achieving significant change. Does this discourse somehow represent a return to the public dimension of the role of architecture and of the architect in our country? The social dimension that Elemental has imprinted on its architecture is in a way repositioning a role the existed 50 years ago. The very fact that the MOP [Chile's Ministry of Public Works] has invited you to collaborate is an achievement for all architects. Do you feel that you're making a change in this sense? Yes and no. You feel that you've done something different, as something is put in the center of attention. But there is still nothing of what needs to be done to change what we see looking at out of the window at billions of people. More than a turn towards the social, of which we have debated much, I would say that there is a confidence that when going into complex issues that matter we are going to make a contribution. But that necessarily involves risks. In general, if architects do not have a 100% guarantee we prefer not to get involved. The project is chosen and fits well. But if the problem is important—and that is a change of judgment, even if there is a long way to go there—in which we have won 51-49, it was already worth having gotten into. But we must know how to live with the 49 that do not meet the expectation of success. The change is in understanding that you should first identify a problem that matters and then see how to make a difference. And for that, we must comprehend that restrictions are the best thing that can happen. In times of removing there must be adding, because the greater the complexity, the greater the need for synthesis. A paper is linear, from up to down, from left to right. Instead, a proposal is all simultaneous, and that capacity to synthesize forces so opposed is tremendously powerful.  © Álvaro González © Álvaro González Is that what your Pritzker Prize recognizes? If something has happened with the Pritzker it is not so much having won it, but rather with what type of projects. Naturally, architecture can get into important matters, putting itself back on the radar as the type of profession that you go to when you have a complex problem. The change is to make society feel that you can contribute on your own terms. To the extent that we can demonstrate that we are not an extra cost but an added value, we will be called back for complex and intersecting problems. The most emblematic case that we have touched in Elemental is Constitución. There was an initial question—how to protect the city against a tsunami—but with the process of participation in the community, we understood that this was less than a quarter of the question. There were other dimensions that should be answered: protection against floods and not only against tsunamis; a deficit of public space, of places where you can spend your free time; and construction of an identity associated with access to the river, because it was the nature and not the fallen buildings that constructed the identity. If you didn't understand that the question had four parts, you would have answered the wrong question correctly. When you analyze that the project resulted in a forest of mitigation between the city and the sea with a cost of US$48 million versus the US$30 million that it would have cost simply to annex and make a ground zero, or US$42 million that a wall would have cost, true, from that point of view it's an extra cost. But when you understand the four variables to which to respond and that the existing projects in the public investment system for the same place sum to US$52 million, what made the design was to save US$4 million because you understood that the problem was more complex. If one is able to demonstrate that proposed value, instead of being called only when there is money and time, you will be who they call when there is no money or time. The Battle of VeniceIs this the seal you were looking to put on the Venice Biennale with "reporting from the front"? Does it mean that to give an adequate response even to the questions that may be wrong? To identify questions that matter and give good answers costs money, is complex, difficult, and even thankless. It implies a true fight, the battle. And suppose that those who front these battles can share how they've achieved success in a value proposal, like in the case of Constitución. We look to share cases, tools, strategies, experiences, so that when returning to your place of origin you do so with more weapons, with dimensions that perhaps you never imagined would be pertinent to your place of origin. To be able to anticipate seeing a problem that today does not exist in your reality, is latent... If you share these conflicts you have anticipatory capacity, and eventually you share knowledge that's replicable in other contexts. More than sharing research, experiences are needed. That is reporting from the front. How was the call received? Did people respond according to what you had visualized? The title functioned well, something like "if the shoe fits." One hand orders: we speak about difficult things, of disputes and of what you did to take charge. But also the call is sufficiently ample for all the problems to have room: issues of immigration, the environment, the economy... Immigration in Europe is not an issue of architects, it affects people in all those countries who have immigrants and who are going to want to go see in the Biennale what ideas exist to tackle it. And it also alludes to place of origin: what could you do to change the conditions of inequality that drive the displacement of the population. In general, it worked because it has triggered issues that are the discussion of societies, not just of architects. In any case, I want to focus the call on the quality of the built environment, not even architecture, because it includes public spaces, infrastructure, and even the surrounding territory as well. And it is the quality of the built environment that, through our efforts, can contribute to the quality of life, just like there are others who design economic policies or social networks or scientific inventions. Not only emergencies, catastrophes, or humanitarian crises destroy the quality of life, also the mediocrity of city peripheries in Europe or the banality of the construction in the United States, there are thousands of examples, each place can report which are the conditions that do not allow quality to be delivered to the built environment and consequently impair the quality of life...  © Álvaro González © Álvaro González Of today's architects, who do you consider relevant for the quality of their responses to challenges like these? Again, in different dimensions, architects who tried to synthesize or encompass components that weren't evident. Shigeru Ban enters fields apparently alien to the architect, like that of the refugees in Africa. In itself, taking care of an African child is not a guarantee of quality, but you have to make, through the medium of architecture, some contribution. And the capacity of Ban is to make a difference by means of design. Not necessarily everything is humanitarian. Following with the Pritzker, in Peter Zumthor, the intensity and quality of his architecture gives a lasting answer to sustainability, that although it is not cheap implies a kind of moral reserve in terms of resisting the passage of time. It is concerned with various dimensions, you could say it is a spectrum of art. The same with Kazuyo Sejima, who cleans a project until there is nothing left. Her architecture is not minimalism, because what she synthesizes is the answer, not the question. Souto de Moura is another capable of integrating a manner of making that has consequences on the manpower it requires, or on resources that are the same as always but used in a surprising way. Of Wang Shu, the Ningbo museum in China is one of those moments in which someone manages synthesis through the manner of construction, using tiles and bricks from the demolition around the building, redefining the typology of a museum. If you only have formal quality, fantastic, it is a way of contributing, but it is not sufficient. The desire is to enter into themes that are very important and whose benefit reaches the largest quantity of people possible. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Open Source House / studiolada architects Posted: 20 Jul 2017 02:00 AM PDT  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte

© Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte From the architect. Architecture for all! This project of a home for a retired couple was born from research on financial optimisation through rationalisation and radicalisation of the design.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte At 1250 € pre-tax per square meter for the residential area, the project places itself in the financial reality of the demand and the offer of the manufacturers of individual houses in France.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte The plan and the cross sections are based on a rational 1 by 1 meter grid: measuring 9 by 9 meters on the ground floor and 9 by 4 meters on the first floor.  Model Model The "generosities" are precisely selected and distributed: height and light for the living areas (living room, mezzanine) and reasonable volumes for the more intimate areas (bedroom, bathroom, kitchen).  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte The living areas are connected: the kitchen to the living/dining room, the terrace to the garden. This layout allows the space to expand towards the outside and reinforces the feeling of openness. The ground floor level is also entirely accessible to people with reduced mobility and offers a complete living area, if required.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte The Southern facade is entirely glazed (protected by a pergola, which can support a cover or a climbing plant), whereas the Northern facade is completely blind. The Western gable is designed to be more welcoming whereas the Eastern gable, more retracted, offers intimate spaces.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte The large 36 square meter mezzanine offers multiple layout and occupation possibilities. If necessary, the mezzanine floor can be partitioned to make two closed bedrooms as well as an additional bathroom.  Section / Plan Section / Plan You will not find any plasterboards in this house — they have been replaced by wooden panels that cover the walls, the ceilings and the partitions. This choice allows the elimination of two trades (plastering and painting) and permits the organisation of a time-saving, dry and clean construction site (because the wood panels are cut and varnished in a workshop)  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte The thermal inertia of the inhabited space is reinforced by the screed and prefabricated concrete which are and embedded into the internal post-and-beam structure.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte The envelope is well insulated with sustainable materials: cellulose wadding (20 cm in the walls, 26 cm in the roof) and supplemented with wood fibre (6 cm in the walls and roof)  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte Open source This universal research on the problematic of the "reasoned and universally accessible individual house" is not an architectural feat. It answers very common questions regarding space, comfort, ecology, urbanism in a simple yet precise way.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte Here, we share all our documents regarding the conception of this small project: Plans, sections, facades, details, quantitative aspects, descriptions, cost estimates, site photos and final photos. All this information is collected in an A3 document of about sixty pages. The PDF is freely downloadable from our platform. We hope that by making this knowledge accessible, we can inspire and encourage the projects and ideas of the greatest number.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte This freedom allows us to militate and diffuse the basis of a different way of building: - Frugality and rationality of the plan - Distribution of "generosities" (volumes, lights, materials) - Reasoned constructive systems - Comfort and functionality - Sustainable materials - Local economy: simple and popular procedures available to local businesses - Value of artisanal know-how: carpentry, joinery, roofing… - Questioning the aesthetic clichés of the French individual house. The principle Open Source information, as opposed to patented, intellectual property is fundamental in what we call the "collaborative society": a society based on principles of openness, trust and value-sharing  Detail Detail  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte  Detail Detail  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte  Detail Detail This procedure, in the tone of a "happy sobriety", raises the question of the role and importance of the architect in the concept of shared progress.  © Olivier Mathiotte © Olivier Mathiotte This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Serious Question: Do Architects Learn Enough About Construction and Materials? Posted: 20 Jul 2017 01:00 AM PDT  © Leewardists © Leewardists Have you ever visited a worksite and thought, "Wow, this contractor knows a lot more about construction than I do"? Have you had to change your original design because it was too difficult to construct or because it exceeded the budget? Do you think you're good at creating well-designed, efficient spaces but you're not so good when it comes to resolving the project's details? Chances are you've found yourself in one or more of these situations, especially if you are a recent graduate. And depending on where and how you were educated, most students learn about construction and materials as it relates to the particular projects they are designing in school. Some people dedicate their career to the construction side of things--choosing classes, studios, and jobs that are focused on more technical, real-world training; others decide to focus their studies on urbanism, landscape architecture or the history of architecture. Finally, it also highly depends on the specific strength and concentration of the school you attend. In spite of the differences that make our profession one rich in diverse interests and allows us to create many different kinds of buildings, the educational deficit (as it relates to materials and construction), prevents us from perhaps exercising the most significant parts of our job: the architect's ability to bring designs to life. Because of this, we wanted to ask our readers to tell us about their experiences and opinions regarding what they know or don't know about the more technical side of architecture. If, from the first year of architecture school, we were made aware of the characteristics and costs of materials, or the real world challenges that arise during construction, would it change the way we design? Would it be easier for us to defend our projects to clients and other professionals? Are you satisfied with your current knowledge of materials and construction techniques? Let us know how you feel in the comments section below. Your opinion may be included in an upcoming article about! * Image via The Leewardists. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| How Earthbags and Glass Bottles Can 'Build' a Community Posted: 19 Jul 2017 11:00 PM PDT

A design by C-re-a.i.d. for a Maasai village in northern Tanzania, is a morphological response to the imposed need to settle, using sustainable, local and accessible materials to redefine its construction culture. The project is built by a series of earthbags and glass bottles that in addition to generating private and comfortable spaces, allow a quick and easy construction.  © Freya Candel © Freya Candel From the Architects. C-re-a.i.d. -Change Research Architecture Innovation Design- is a non-profit organization operating in northern Tanzania since 2012. Through experience and analysis, we uncovered a rapid changing building culture, poor living situations and the use of unecological materials. We explore the possibilities of architecture to promote long-term ecological and affordable building.  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille Our projects are located in different villages in the surroundings of Moshi, one of them being Maji Moto - a Maasai village. Tanzanian government decided to restrict the nomadic lifestyle of Maasai people, and forced them to settle down. Since they were used to trekking, up to this day, their structures reflect a certain degree of temporality. Ever since Maasai were forced to settle, they have struggled to redefine their building culture in order to align it with their new lifestyle; local communities are caught in between tradition and modernization.  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille Burned bricks, glass, and corrugated sheets replaced mud, sticks, and leaves. Although this newly introduced way of building complies with their needs and wishes, it doesn't align with the context. In order to produce the burned bricks, trees need to be cut and this means the area suffers from the clear deforestation that has been going on for some time. Arid land can be seen as the direct result of this process and eventually, agriculture will become close to impossible in the near future.  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille We try to turn things around by doing research and informing the local community of the consequences of their actions. The technique of earthbags offers local craftsmen an alternative for the burned bricks since it uses only sand and soil. Not only does this way of building present a more sustainable material, it also offers additional comfort to the living conditions because of its thermal mass.  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille The family’s living condition was mainly defined by a lack of privacy. That is exactly why the design focuses on the notion of living-together-apart. The concept consists of three intertwining circles: one for the mother, one for the daughter, and a common area in between.  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille  © Mathias Cornille © Mathias Cornille Building with earthbags lends itself perfectly to the design of circular units, as no lateral support is required. Furniture was incorporated in the structure and glass bottles were used to add light to the interior.  Cortesía de C-re-a.i.d. Cortesía de C-re-a.i.d. The labour intensive building method of earthbags wouldn’t have been an option if it wasn’t for the helping hands of 15 students and 4 teachers of a Belgian secondary school (VTI Brugge). This close collaboration between future craftsmen and architects turned design into reality in no time.  Cortesía de C-re-a.i.d. Cortesía de C-re-a.i.d.  Cortesía de C-re-a.i.d. Cortesía de C-re-a.i.d. Project Name: Old Habits, New Ideas This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| You are subscribed to email updates from ArchDaily. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar