Arch Daily |

- MR&MRS White Store / Paulo Merlini arquitetos

- School Jean-Monnet / Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architects + CDA Architectes

- The Farm of 38° 30° / Slash Architects + Arkizon Architects

- Al Hilal Bank Office Tower / Goettsch Partners

- Fongster / Kite Studio Architecture

- Dongziguan Affordable Housing for Relocalized Farmers / gad

- The Pavillion / Jorge Hrdina Architects

- Michael Wolf Explains the Vision Behind his Hong Kong Photo Series, “Architecture of Density”

- Pole House / DIN Projects

- These Graphics Imagine Unrealized Architectural Plans as Beautiful Snowflakes

- Puertos Escobar Football Club / Torrado Arquitectos

- 6 Practices Recognized as Social Design Innovators by Curry Stone Design Prize

- Lima Convention Center / IDOM

- Architectural Research: Three Myths and One Model

- Municipal Gym of Salamanca / Carreño Sartori Arquitectos

- Venice Isn't Sinking, It's Flooding – And It Needs to Learn How to Swim

- BigBek Office / SNKH Architectural Studio

| MR&MRS White Store / Paulo Merlini arquitetos Posted: 03 Jan 2017 09:00 PM PST  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG

© Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG Objects are crystalized ideas, the better the interconnection of ideas the better the object and most pertinent it is. Sometimes is functionality is so pertinent that the aesthetic value gets forgotten. Here at the office we like good ideas and like do value them. Recover these design "Cinderella's" and bring them back, so that people can understand their aesthetic value.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG As such we explored some potential object that could help us to built an appealing environment and that preferentially was in those conditions, and we found it, The hanger.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG We flooded the space with more than a thousand hangers that, because of their intrinsique aesthetic value involves the user in a unique ambient.  Model Model Hangers are almost renegade in the store design, their functional pertinence is such that they're almost always thrown backstage. The same characteristic that made them a global success made them follow into banality. A victim of their own success. We distributed the hangers all over the space, divided in equidistant points. When viewed from above it seems a pixelated screen with four hundred points distributed over 80.00sq/m  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG By working with the threads altimetry we understood we could recreate any space throw the negative of the original space. We wanted one that for his cultural relevance could become immediately recognizable and above all was able to valorize cloths and our base element.  Ceiling Floor Plan Ceiling Floor Plan We´ve studied innumerous forms and realized that the formal power of the naves of a cathedral was all we wanted. For one it had the recognizable force, and on the other hand it is a space drawn for dignify an valorize, it would automatically throw the observer into an aura of contemplation.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG So, when the observer enters, it´s automaticly involved by the naves silouete, the threads tension caused by the clothes weight makes gravity force almost palpable, directing our eyes up. Cloths flow throw space, their the elements that give consistency to the intervention. Their the foundations of the cathedral.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG If empty space defines the archetype of a cathedral nave, the rest is awash with light. A serie of equidistant lights project light up making it more vertical and defining the space rythmics. Light is reflected in the threads white colour and give light a sense of materiality.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG We wanted a very desaturated space in order to highlight clothes colour, making them the lead actor. One other particularity is that the client can hang a specific cloth wherever he want in order to evidenciate.  © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG © Fernando Guerra | FG+SG This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| School Jean-Monnet / Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architects + CDA Architectes Posted: 03 Jan 2017 07:00 PM PST  © Julien Lanoo © Julien Lanoo

© Julien Lanoo © Julien Lanoo From the architect. In cooperation with Colas Durand Architectes, Dietrich | Untertrifaller built this middle-school in Broons/Bretagne. 16 classrooms and 9 theme specific rooms as well as an entertaining area for after school activities provide spaces for 600 students.  © Julien Lanoo © Julien Lanoo  Ground Level Ground Level  © Julien Lanoo © Julien Lanoo  Level 1 Level 1  © Julien Lanoo © Julien Lanoo The building itself is constructed with concrete and wood elements. The facade of the main floor is covered with the famous local stone, the two upper floors impress with a wood facade. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| The Farm of 38° 30° / Slash Architects + Arkizon Architects Posted: 03 Jan 2017 06:00 PM PST .jpg?1483435880) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography

.jpg?1483435243) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography Identity .jpg?1483435428) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography The Farm 38° 30°, an iconic boutique dairy factory, derives its name from the coordinates of the site it is located in, the "38° 30° Valley of Art" in the village of Afyon Tazlar, in the province of Afyonkarahisar in Central Turkey. Located at the entrance of the valley, this dairy factory offers degustation for visitors, all the while exhibiting the production process of the dairy products of the farm.  Isometric Isometric While ensuring maximum efficiency for the production line as in a "classical" cheese factory building, the boutique factory adopts a more contemporary attitude via its monumental form. The building wraps around an inner green courtyard and opens itself to the exterior via its large welcoming canopy. The building typology is upgraded from the status of a simple production space to that of a cheese showroom / museum. .jpg?1483435792) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography Form and Program The building wraps the linear production process and spaces in an ellipse enclosing an inner courtyard. From this courtyard within, all sequences of the production can be observed in 360° degree by the visitors. The transparency of the façade lets us peek into the production spaces while the staff animates the whole.  Diagram Diagram Interrupting the closed ellipse, the building entrance is open to the exterior and invites visitors into the inner courtyard. The sheltered entrance orients the visitors to either the main sales department or the green courtyard, where cocktails and events are organized. .jpg?1483435742) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography The main entrance's canopy is part of a large concrete slab roof that is formed from the geometric position of the elliptical building itself. The roof is at its maximum height over the entrance spaces, and gradually lowers to reach its minimum height over spaces such as cold storage rooms, therefore optimizing the volume under it and increasing efficiency of insulation, temperature and air control in the building. .jpg?1483435068) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography The factory optimizes the linear composition of the spatial necessities. The materiality of the façade reflects the degree of privacy and interest of the various spaces. The entrance is fully open, followed by the sales office and the production spaces of the factory, both very transparent. Moving on to more private spaces, the composition of the materials on the façade gradually offers less transparency. Corten steel sun blinds render the last spaces, used by staff, semi-transparent. The external façade of the building is enriched by vertical slices opening to the surrounding countryside vista, all the while allowing controlled natural light according to each specific room's requirements. .jpg?1483435386) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography Engaging with Nature and Natural Materials The Dairy Factory engages with the surrounding nature through its use of natural materials and natural tones. Weaving the green environment and landscape towards the inner courtyard, the building offers a cozy environment enabling various activities for both its visitors and staff. .jpg?1483435563) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography The use of local materials such as natural Afyon stone is enriched by the addition of Corten steel in the details, emphasizing the contemporary industrial identity of the building. The exposed concrete, the natural stone, the transparent glass and the Corten details combined onto the elliptical form of the building reveal a contemporary attitude anchored to its site and location. .jpg?1483435839) © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography © Alp Eren - ALTKAT Architectural Photography This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Al Hilal Bank Office Tower / Goettsch Partners Posted: 03 Jan 2017 02:00 PM PST  © Lester Ali © Lester Ali

© Lester Ali © Lester Ali From the architect. This 24-story office tower serves as the flagship commercial development for Al Hilal Bank, a progressive Islamic bank in Abu Dhabi. Located on Al Maryah Island, the emirate's designated new CBD according to its 2030 master plan, the building is designed to attract leading national and international companies with Class A office space of the highest quality. The building features efficient, column-free floor plates; floor-to-ceiling glass; and the latest technology and amenities, filling a void in the developing market.  © Tom Rossiter © Tom Rossiter Challenged to define a distinctive image that would reflect the bank's progressive brand while also setting an international aesthetic, the design defines a bold, contemporary tower that shifts in massing as it rises. The podium contains retail space and a dramatic three-story transparent lobby to the north, with pedestrian arcades on the east and west. Three cubical masses sit atop the podium, stacked like shifted blocks. Designed to set the building apart from other towers on the island, these forms derive their interest from recessed corners that are offset from each other. In addition, the building's façade changes at the created voids to accentuate the shifted aesthetic. Orange accents highlight the voids while reinforcing the bank's branding both day and night.  © Lester Ali © Lester Ali Intended to convey a timeless, elegant image, the façade is composed of an aluminum-and-glass curtain wall system with glass and notched metal-spandrel elements and vertical glass fins that enhance the building's verticality while also providing subtle shading. Designed to achieve an Estidama 1 Pearl sustainability rating, the tower offers maximum transparency, with floor-to-ceiling, high-performance glass providing spectacular views for occupants while significantly increasing interior daylight.  © Lester Ali © Lester Ali A landscaped park and reflecting pool along the building's western façade draw pedestrian traffic by creating an inviting, shaded urban space. Seating for tenants and visitors helps further complement the outdoor setting.  © Tom Rossiter © Tom Rossiter This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Fongster / Kite Studio Architecture Posted: 03 Jan 2017 12:00 PM PST  © David Yeow © David Yeow

© David Yeow © David Yeow The design for Fongster is very much driven by the Client's passion for cars and bikes. With the brief requiring the residence to fit a spacious and well-equipped garage on top of the standard dwelling requirements, it was hard not to make the garage as a feature of the house. It takes centrestage, providing the sense of arrival and welcome into the house. A verandah that is an extension to the master suite at the second floor 'hovers' above it, framing the entrance-garage. .jpg?1483049235) Floor Plans Floor Plans Fongster sits on a long and narrow plot and as with other plots of similar nature, one of the main challenges is to ensure efficient circulation given the spatial brief. Several strategies have been adopted to tackle this. Firstly, the plan meanders at the living room (first floor) and master suite (second floor) to break an otherwise long and straight circulation path to the rest of the house. This also provides these spaces with deeper and layered vistas, facing away from the harsh West sun and direct views from the neighbouring public housing.  © David Yeow © David Yeow Secondly the central semi-open terrace in the middle of the house punctuates the spatial configuration. It is a break-out space separating the living and the dining, providing an informal spill-out space for both rooms. This spatial punctuation is also the point for vertical circulation. One of the intentions of placing the stairwell in the middle of the house is to avoid creating unnecessarily long and inefficient corridors. The stairs lead one to the common bedrooms on one side and the master suite on the other. The interstitial central space assumes the communal study area.  © David Yeow © David Yeow Upfront at the garage, a spiral staircase connects the entrance straight to the master suite verandah, allowing the client direct access to his collection. This verandah is an interpretation of the 'ambin', a raised entrance porch found in traditional Malay 'kampong' house. Just like the 'ambin', the verandah is a space for informal gatherings with neighbours and close friends. As the house sits at the end of the street, the verandah commands unobstructed views of the tree-lined street and the open field at the rear. The form of the house assumes a dynamic stance, reflecting the spatial maneuvers within the tight narrow site and the subtle reference to the owner's passion for all things fast and svelte.  © David Yeow © David Yeow Product Description. The BendPak car lift system provides an efficient and compact solution for the garage, given the floor-to-ceiling constraint. It is not bulky and heavy-looking and therefore it does not compromise the overall aesthetics of the garage. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Dongziguan Affordable Housing for Relocalized Farmers / gad Posted: 03 Jan 2017 11:00 AM PST  Courtesy of gad Courtesy of gad

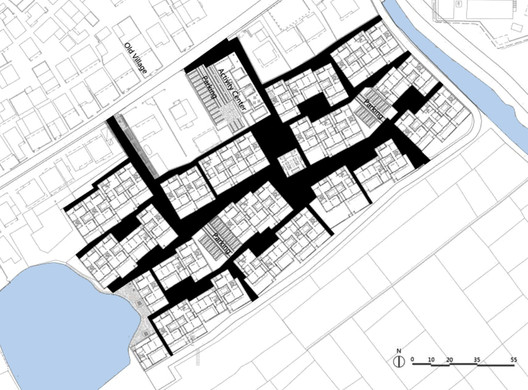

Courtesy of gad Courtesy of gad The project tackles a current social issue within the urbanization process in China: the increasing urban-rural disparity. Currently the living conditions in large part of rural China are poor, for instance in Dongziguan Village in Fuyang Hangzhou, most of the farmers still live in the aged housings of disrepair. Local Government in Fuyang District of Hangzhou decided to fund an exemplary affordable housing project in Dongziguan Village aiming at improving living condition for relocalized farmers.  Courtesy of gad. ImageBird's view Courtesy of gad. ImageBird's view During the design process, architects conducted investigations and meetings to communicate with different families of the relocalized farmers for first-hand information including their living habits. This award-winning project seeks to organize the buildings in the vernacular style of a courtyard typology, a traditional local morphology. The design of the courtyard makes it vary into four prototypes that learnt from the tradition and its diversity. The prototypes could be developed into clusters, which later grow into a larger rural settlement.  Courtesy of gad Courtesy of gad The plan layout based on the common requirements from the relocalized farmers tries to balance the traditional rural life-style and high-quality modern living condition. The design of the housings is not a carbon-copy of the local historic buildings, but abstracts and refines the features of the traditional local architecture with contemporary understandings, and then incorporates them into the design of the new housings.  © Li Yao, Chunle Liao © Li Yao, Chunle Liao  Site Plan Site Plan  Courtesy of gad Courtesy of gad The design intention of gad is dedicated to the preservation of the vernacular morphology of rural settlements that maintain original local living style and more importantly resists the current widely-criticized Chinese residential form consisted of bar-shaped highrises. Also we fights for the best building quality within the very low budget and explores contemporary ways of representing local traditional architectural characteristics. This project opens the dialogue of how the architects can help build and improve the countryside with the support from the government.  © Li Yao, Chunle Liao © Li Yao, Chunle Liao  Ground Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan  © Li Yao, Chunle Liao © Li Yao, Chunle Liao This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| The Pavillion / Jorge Hrdina Architects Posted: 03 Jan 2017 09:00 AM PST  © Ross Honeysett © Ross Honeysett

© Ross Honeysett © Ross Honeysett From the architect. The Pavilion is an entertaining space for family and friends. This crafted contemporary building sits on a double block in Mosman, Sydney, with views of ships coming through the iconic Sydney Heads. The Pavilion shares the block with its older sister – a 19th century Queen Anne heritage house whose intricately hand crafted details are complemented by the form and materiality of The Pavilion.  Site Plan Site Plan Craftsmanship is one of the connecting forces between the existing building and The Pavilion, bridging centuries of architecture. The base of the federation house is grounded by sandstone. Likewise, The Pavilion rises from the earth with a structural core of rough- hewn sandstone. Work to the existing home included a crafted renovation in its original Queen Anne style. The result is a seamless transition between old and new.  © Ross Honeysett © Ross Honeysett The contemporary pavilion is defined by a technological and engineering feat – a sculpted concrete beam that cantilevers 15 metres either side of the structural core of the building. It floats over the indoor/outdoor entertaining space and front garage. The beam and the translucence of the ground floor of The Pavilion create a sense of weightlessness. The land and curtilage surrounding the Queen Anne home blend seamlessly with the interior spaces blurring the line between inside and out. The custom folding beam required the help of a skilled ship builder from Nowra, NSW, who created the four separate moulds for the formwork using solid MDF lined with a smooth interior of fiberglass. It is fitting that a ship builder created the formwork moulds as the original dwellers of the property were ship merchants – this heritage became a reference point for the ship-like form of the beam.  Ground Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan  First Floor Plan First Floor Plan A tour inside The Pavilion reveals the enduring, natural and honest materials that define the space. A raw palette that includes dappled concrete beams, stained Blackbutt timbers, frameless glass doors and smooth honed sandstone floors are laid throughout the ground level. Oak treads form the winding staircase, which lead to a small self-contained apartment and media room above and an underground cellar below.  © Ross Honeysett © Ross Honeysett The Pavilion is roofed with a simply designed and generously planted accessible deck and roof garden, which provides a space to be enjoyed by family and friends while overlooking the surrounding tree canopies and views over Sydney Harbour  © Ross Honeysett © Ross Honeysett This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Michael Wolf Explains the Vision Behind his Hong Kong Photo Series, “Architecture of Density” Posted: 03 Jan 2017 08:10 AM PST

In this short film from Yitiao Video, photographer Michael Wolf explains the vision behind his momentous photo series, "Architecture of Density," in which he captures the immense scale and incredible intricacies of the city of Hong Kong. After living in city for 9 years and travelling abroad to work, Wolf describes the somewhat unpleasant circumstances which led him to turn his attention to his own environment. Via Yitiao Video. Capturing Hong Kong's Dizzying Vertical Density This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 03 Jan 2017 07:00 AM PST  Courtesy of DIN Projects Courtesy of DIN Projects

Courtesy of DIN Projects Courtesy of DIN Projects The Pole House is a year round cottage designed for a couple and their son on a heavily wooded site in the Manitoba Interlake, two and a half hours North of Winnipeg. The cottage lot, obtained through the provincial cottage lot lottery system, has Lake Winnipeg frontage, although a provincial easement limits the cottage's proximity to the water.  Site Plan Site Plan The site's geology is limestone bedrock covered by a shallow layer of overburden. The low profile of this landscape combined with the porous nature of the overburden results in an extremely high water table on the site. This condition necessitated a unique, dock-like crib structure to accommodate high water and freeze-thaw heave. The foundation is a steel pole (recycled gas pipe) grid that extends below the ground surface, and is drilled into the subterranean bedrock.  Courtesy of DIN Projects Courtesy of DIN Projects To suit its dense forest context, Pole House is designed as a vertical wood platform structure that floats above the ground on thin steel pipe columns. The resulting tower typology enables views to the lake through the forest. Three economical floor plates are stacked, progressing from most public to most private. A stair winds around each floor plate contained within a simple rectangular form.  Section Section The cottage interior is primarily left exposed, revealing its wood frame, studs and plywood sheathing. Materials and services are matter of fact and raw in their presentation and use.  Courtesy of DIN Projects Courtesy of DIN Projects A singular rigid foam insulation jacket strives for thermal efficiency, and internal ducting allows for air to be controlled and distributed vertically. A cast iron wood stove in the middle of the cottage is the primary heating source. Interior spaces are informal, meant for both hanging out and hiding away.  Elevations Elevations  Floor Plans Floor Plans  Model Model This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| These Graphics Imagine Unrealized Architectural Plans as Beautiful Snowflakes Posted: 03 Jan 2017 06:00 AM PST  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS Much like snowflakes, the most beautiful architectural plans consist of complex relationships between geometries – and no two are exactly alike. In this spirit, KOSMOS Architects has created a series of planimetric graphics of some of the most notable architectural projects to have disappeared from our world in celebration of the New Year. "Sometimes architecture isn't everlasting, and is as ephemeral as snowflakes on a Christmas tree. On our Happy New Year poster we have collected some fairy, radical, and utopian plans, which were either never built or have already disappeared. We hope these 'snowflakes' will inspire you in 2017!"  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS  Courtesy of KOSMOS Courtesy of KOSMOS To download a high-res poster of the "snowflakes," click here. Via KOSMOS Architects. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Puertos Escobar Football Club / Torrado Arquitectos Posted: 03 Jan 2017 05:00 AM PST  © Fernando Schapochnik © Fernando Schapochnik

© Fernando Schapochnik © Fernando Schapochnik From the architect. The soccer club of Ports required a series of programs in principle dispersed, what tries the project is to order the programs and circuits of routes. The needs of the club were a parking area, locker rooms, shade area, multiple uses lounge, billboard and barbecue for third time. All these activities in principle individual and without cohesion, make up a unique building of mixed uses, flexible, and variable transparencies.  © Fernando Schapochnik © Fernando Schapochnik  General Plan General Plan  © Fernando Schapochnik © Fernando Schapochnik The general order of the project is centered on arranging the parking area parallel to a single linear building of 60 mts long that concentrates all the functions. Thus, the programs are sequentially arranged. Machine rooms, changing rooms, billboards in semi-covered, multipurpose room, all programs are resolved within free width of 6 meters. Flexible space, without intermediate supports, solved by two parallel metallic porticos on the perimeter and pre-molded slabs of free light to cover.  © Fernando Schapochnik © Fernando Schapochnik This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| 6 Practices Recognized as Social Design Innovators by Curry Stone Design Prize Posted: 03 Jan 2017 04:30 AM PST  © José Bastidas / Pico Collective Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize. ImageCustomized size and shape basketball court. La Ye 5 de Julio, Petare, Caracas © José Bastidas / Pico Collective Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize. ImageCustomized size and shape basketball court. La Ye 5 de Julio, Petare, Caracas In the past 10 years, the Curry Stone Design Prize has grown to become one of the world's preeminent awards honoring socially impactful design professionals and the influence of design as a force for improving lives and strengthening communities. This year, in honor of the prize's 10th anniversary, the Curry Stone Foundation will acknowledge the largest group of influential practices yet, recognizing 100 firms over the next twelve months as members of the "Social Design Circle." Each firm will be profiled on the award website, as well as participate in the foundation's new podcast, Social Design Insights, beginning on January 5th, 2017. "In the past ten years the Curry Stone Design Prize has been recognizing some of the most impactful and inspirational international practices," says Emiliano Gandolfi, the Prize Director. "Their work is part of a larger movement of individuals and groups who see design as a necessary tool to make our societies more just, environmentally sustainable, and socially inclusive. We formed the Social Design Circle to illustrate the significance of this movement and to share with a wider audience the great potential of these transformative practices." The Social Design Circle recipients will be announced on a monthly basis within thematic categories based on their accomplishments. For the month of January, 6 firms were recognized under the theme of "Should Designers be Outlaws?":  © Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize © Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize Mark Lakemen (City Repair Project)  © Mark Lakemen (City Repair Project). Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize © Mark Lakemen (City Repair Project). Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize  El Trébol: cultural community space. Capoeira workshop. Bogotá, 2015. Image © Arquitectura Expandida. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize El Trébol: cultural community space. Capoeira workshop. Bogotá, 2015. Image © Arquitectura Expandida. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize  © José Bastidas / Pico Collective. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize. ImageCultural production unit ZPG. Reused Components. Guaraca, Carabobo, Under Construction © José Bastidas / Pico Collective. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize. ImageCultural production unit ZPG. Reused Components. Guaraca, Carabobo, Under Construction  2012 Marcel House. Recycled geodesic sustainable house, Spain. Image © Ctrl+Z-Luca Stasi. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize 2012 Marcel House. Recycled geodesic sustainable house, Spain. Image © Ctrl+Z-Luca Stasi. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize ![Araña [Spider], Seville 2011. Portable space's protoype. Image © Recetas Urbanas. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize Araña [Spider], Seville 2011. Portable space's protoype. Image © Recetas Urbanas. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize](http://images.adsttc.com/media/images/586b/d548/e58e/ceb3/af00/0016/medium_jpg/Aran%CC%83a__Seville_2011_credit_Recetas_Urbanas.jpg?1483461942) Araña [Spider], Seville 2011. Portable space's protoype. Image © Recetas Urbanas. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize Araña [Spider], Seville 2011. Portable space's protoype. Image © Recetas Urbanas. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize These 6 firms will feature in January episodes of the Social Design Insights podcast, co-hosted by Prize Director Emiliano Gandolfi and award-winning author, architect and post disaster expert, Eric Cesal. The pair will engage in conversation with movement leaders over the next 12 months in the following issues:

"Social Design Insights will be a forum to hear from the Social Design Movement's leading practitioners about their own methods, in their own words. By drawing dozens of practitioners from all fields into one conversation, we hope that we can examine Social Design's current challenges and future potential," says Eric Cesal. The podcast will air each Thursday on the Prize's website and will be available through iTunes, Android and RSS feeds beginning in January with Teddy Cruz, Santiago Cirugeda (Recetas Urbanas), Arquitectura Expandida, Stalker, and Mark Lakeman (City Repair Project). At the beginning of each month, new honorees of the prize will be announced to the public. To learn more about the prize and about this month's recipients, visit the Curry Stone Design Prize website, here. News via Curry Stone Design Prize. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 03 Jan 2017 03:00 AM PST  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz

© Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz From the architect. The project and construction of the Lima Convention Centre (LCC) is contextualized by the agreement between the Peruvian State and the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to hold in Lima the 2015 Board of Governors.  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz Strategically located in the Cultural Centre of the Nation (CCN) – next to the National Museum, the Ministry of Education, the new headquarters of the National Bank or the Huaca San Borja – the design of the LCC was to satisfy four strategic objectives: being a cultural and economic motor for the country, representing a meeting place at the heart of the city enrooted in the collective Peruvian culture, turning into a unique, flexible and technologically advanced architectonic landmark and finally, triggering the urban transformation of the CNN and its surroundings.  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz The near 15,000 m2 of net area correspond to the 18 multipurpose convention halls, their sizes and proportions varying from 3,500 m2 to 100 m2, which allow for up to 10,000 people to attend simultaneous events. The rest of the programme is completed by four underground car-park floors as well as several uses above ground that complement the conference rooms. These would include areas for translation and general management of the centre, stockrooms and toilets, workshops and areas for maintenance and material distribution, kitchens and dining areas, exhibition halls, cafeterias and relaxation areas. This all generates a total built up area of 86,000 m2.  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz The urban proposal situates the access to the building on the north end, therefore encouraging the future development of the Culture Boulevard. The general volume is organized into three time-physical strata clearly differentiated, symbolically related to the country's history, time and memory: The present is represented by the great internal void – Nation Rooms – which harbours the two transformable rooms of about 1,800 m2, one of which can open up entirely to the city by clearing its perimeter of the acoustics panels that make it up, generating a sheltered urban plaza over 2,500 m2.  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz The past, the heart of the project, is an outdoor area inspired by a great huaca – Lima Lounge – generated naturally by the disposition and the difference in height of the convention halls.  Cross Section Cross Section  Cross Section Cross Section The future is a great vitreous volume – International Room of Nations. It's a highly technical conventions facility which invites the rest of the world to come to Peru for its entrepreneurial capacity and its promising future.  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz The operative and functional flexibility are keys to the comprehensive design of the LCC and are orientated towards maximizing the economic and social success of the project. Nearly all rooms can be extended or reduced thanks to the acoustic panels that limit them, making it possible to have several spatial distributions.  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz Technically, the mandatory condition by which the great 5,400 m2 room, with capacity for 3,500 people, was to be free from pillars – along with the seismic inconvenience of using propped up structures –, turns the conceptual and structural proposal into a challenge, since it implies putting the great room on the last level. Placing a sheltered volume the size of a football pitch at a height of over 30 m is a challenge to both the structural approach and the building's internal mobility – access and evacuation.  © Aitor Ortiz © Aitor Ortiz This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Architectural Research: Three Myths and One Model Posted: 03 Jan 2017 01:30 AM PST  <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/522408/icd-itke-research-pavilion-2015-icd-itke-university-of-stuttgart'>ICD-ITKE Research Pavilion 2013-14</a>. The annual ICD-ITKE Research Pavilion, completed by students at ICD-ITKE University of Stuttgart, is an example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "Through." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural products. Image Courtesy of ICD-ITKE <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/522408/icd-itke-research-pavilion-2015-icd-itke-university-of-stuttgart'>ICD-ITKE Research Pavilion 2013-14</a>. The annual ICD-ITKE Research Pavilion, completed by students at ICD-ITKE University of Stuttgart, is an example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "Through." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural products. Image Courtesy of ICD-ITKE Jeremy Till's paper "Architectural Research: Three Myths and One Model" was originally commissioned by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Research Committee, and published in 2007. In the past decade, however, it has grown in popularity not just in the UK, but around the world to become a canonical paper on architectural research. In order to help the paper reach new audiences, here Till presents an edited version of the original. The original was previously published on RIBA's research portal and on Jeremy Till's own website. There is still, amazingly, debate as to what constitutes research in architecture. In the UK at least there should not be much confusion about the issue. The RIBA sets the ground very clearly in its founding charter, which states that the role of the Institute is:

The charter thus links the advancement of architecture to the acquirement of knowledge. When one places this against the definition of research given for the UK Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), "research is to be understood as original investigation undertaken in order to gain knowledge and understanding", one could argue that research should be at the core of RIBA's activities. This essay is based on the premise that architecture is a form of knowledge that can and should be developed through research, and that good research can be identified by applying the triple test of originality, significance and rigor. However, to develop this argument, it is first necessary to abandon three myths that have evolved around architectural research, and which have held back the development of research in our field. Myth One: Architecture is just architectureThe first myth is that architecture is so different as a discipline and form of knowledge, that normal research definitions or processes cannot be applied to it.[1] "We are so unlike you," the argument goes, "that you cannot understand how we work." This myth has for too long been used as an excuse for the avoidance of research and the concomitant reliance on unspecified but supposedly powerful forces of creativity and professional authority. This myth looks to the muse of genius for succor, with the impulsive gestures of the individual architect seen to exceed the dry channels of research as the catalyst for architectural production. The problem is that these impulses are, almost by definition, beyond explanation and so the production of architecture is left mythologized rather than subjected to clear analysis. Architecture is limited to a form of semi-mystical activity, with the architect, as heroic genius, acting as the lightning rod for the storm of forces that goes into the making of buildings. This first myth also treats architecture as an autonomous discipline, beyond the reaches or control of outside influences, including those of normative research methodologies. This leads to the separation of architecture from other disciplines and their criteria for rigor. Self-referential arguments, be they theories of type, aesthetics or technique, are allowed to evolve beyond the remit or influence of accepted standards, and research into these arguments is conducted on architecture's own terms. The myth that architecture is just architecture, founded on the twin notions of genius and autonomy, leads eventually to the marginalization of architecture. A knowledge base is developed only fitfully and so architecture becomes increasingly irrelevant and, ultimately, irresponsible.  Research such as <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/782902/these-churches-are-the-unrecognized-architecture-of-polands-anti-communist-solidarity-movement'>Architecture of the VII Day's study of Polish churches</a> is a clear example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "In." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural performance. Image © Igor Snopek Research such as <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/782902/these-churches-are-the-unrecognized-architecture-of-polands-anti-communist-solidarity-movement'>Architecture of the VII Day's study of Polish churches</a> is a clear example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "In." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural performance. Image © Igor Snopek Myth Two: Architecture is not architectureThe second myth works in opposition to the first and argues that in order to establish itself as a credible and 'strong' epistemology, architecture must turn to other disciplines for authority. Architecture is stretched along a line from the arts to the sciences and then sliced into discrete chunks, each of which is subjected to the methods and values of another intellectual area. For example, the highly influential 1960s Oxford Conference on architectural education looked to scientific research as the means of establishing architecture within the academy. More recently architectural theory has immersed itself in the further reaches of critical theory in an effort to legitimize itself on the back of other discourses. In both these cases, and others that also rely on specific intellectual paradigms, architecture's particularity is placed within a methodological straightjacket. In turning to others, architecture forgets what it might be in itself. The second myth, that architecture is not architecture, in editing the complexity of architecture thus describes it as something that it may not be. It is a myth fuelled by the funding mechanisms for research, with the various research councils defining acceptable areas through particular research paradigms, which simply do not fit the breadth of architecture. Interestingly Myth One and Myth Two can and do operate in parallel, often within the same institution. Thus it is common to find the design core of a School of Architecture – playing out myth one - physically and intellectually separate from the 'research' core, with mutual antipathy between the two. Myth Three: Building a building is researchThe third myth is that designing a building is a form of research in its own right. It is a myth that allows architects and architectural academics to eschew the norms of research (and also to complain when those norms are used to critique buildings as research proposals). The argument to support this myth goes something like this:

It is compelling enough an argument to allow generations of architects (as well as designers and artists) to feel confident in saying that the very act of making is sufficient in terms of conducting research, and then to argue that the evidence is in front of all our eyes if we would just choose to look. However, it is also an argument that leads to denial of the real benefits of research, and so it is worth unpicking.

Designing a building is thus not necessarily research. The building as building reduces architecture to mute objects. These in themselves are not sufficient as the stuff of research inquiry. In order to move things on, to add to the store of knowledge, we need to understand the processes that led to the object and to interrogate the life of the object after its completion.  Research such as <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/514003/arup-develops-3d-printing-technique-for-structural-steel'>Arup's investigations into 3D-printed steel</a> is an example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "for." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural products. Image © David de Jong Research such as <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/514003/arup-develops-3d-printing-technique-for-structural-steel'>Arup's investigations into 3D-printed steel</a> is an example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "for." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural products. Image © David de Jong Making Architecture SpeakAgainst these myths, one has to understand that architecture has its own particular knowledge base and procedures. This particularity does not mean that one should avoid the normal expectations of research, but in fact demands us to define clearly the context, scope and modes of research appropriate to architecture, whilst at the same time employing the generic definitions of research in terms of originality, significance and rigor. The normal stretching of the field of architecture along the arts to science line (with the social sciences somewhere in the middle) results in each place along the line being researched according to a particular paradigm and methodology from the research spectrum. This ignores design, which is clearly an essential feature of architectural production; design cannot be so easily categorized as a qualitative or quantitative activity, but should be seen as one that synthesizes a range of intellectual approaches. Architectural research is better described by Christopher Frayling's oft-cited triad of research 'into', 'for' and 'through.'[2] Frayling developed this approach for design research in order to address the specific relationship between design and research. In this model, research 'into' takes architecture as its subject matter, for instance in historical research, or explanatory studies of building performance. Research 'for' refers to specifically aimed at future applications, including the development of new materials, typologies and technologies; it is often driven by the perceived needs of the sector. Research 'through' uses architectural design and production as a part of the research methodology itself. Architectural research may be seen to have two main contexts for its production, the academy and practice. Research 'in' is traditionally the domain of the academy and research 'through' that of practice, with research 'for' somewhere in the middle. Research 'in' has the most clearly defined methodologies and research outcomes, but at the same time is probably the most hermetic. Research 'through' is probably the least defined and often the most tacit but at the same time a key defining aspect of architectural research. It is this area that needs developing most of all. It is vital that neither academic or practice-based is privileged over the other as a superior form of research, and equally vital that neither is dismissed by the other for being irrelevant. ("You are all out of touch with reality," says the practitioner. "You are muddied by the market and philistinism," says the academic). There is an unnecessary antipathy of one camp to the other, which means that in the end the worth of research in developing a sustainable knowledge base is devalued. The key to overcoming this problem lies in communication. Both the academy and practice often do not meet this central test for research: the academy because of its inward looking processes, practice because of its lack of rigorous dissemination. Whilst academic research is subjected to stringent peer review and assessment procedures, it has been argued that this had led to inward-looking results produced more for the self-sustaining benefit of the academic community and less for the wider public and professional good. On the practice side, much of the most innovative research in design and, particularly, technology is founded in practice. However, much of this research remains tacit; it is either, for commercial reasons, not shared with the rest of the community or else in its dissemination through the press is not communicated with the rigor it deserves. For the leading practices intellectual property is what defines them and sustains them, and they understandably are loath to give it away. Research goes on, but silently. The development of architectural knowledge happens but fitfully, and so the long-term sustainability of the profession is threatened. To avoid this, we need to make architecture speak.  Research such as <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/801641/architectures-political-compass-a-taxonomy-of-emerging-architecture-in-one-diagram'>Alejandro Zaera-Polo and Guillermo Fernandez-Abascal's "taxonomy" of contemporary emerging practices</a> is an example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "in." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural processes. Image © Alejandro Zaera-Polo & Guillermo Fernandez Abascal Research such as <a href='http://www.archdaily.com/801641/architectures-political-compass-a-taxonomy-of-emerging-architecture-in-one-diagram'>Alejandro Zaera-Polo and Guillermo Fernandez-Abascal's "taxonomy" of contemporary emerging practices</a> is an example of Christopher Frayling's definition of research "in." In Till's model, this could be categorized as research into architectural processes. Image © Alejandro Zaera-Polo & Guillermo Fernandez Abascal A New Model for Architectural ResearchAs we have seen, the stretching of architecture across separate areas of knowledge does not address the particular need for architectural knowledge and practice to be integrative across epistemological boundaries. Buildings as physical products function in a number of independent but interactive ways – they are structural entities, they act as environmental modifiers, they function socially, culturally and economically. Each of these types of function can be analyzed separately but the built form itself unifies and brings them together in such a way that they interact. Research into architecture thus has to be conscious of these interactions across traditionally separate intellectual fields. In order to give some clarity to the scope of architectural research, these interactions can be divided into three stages:

The first stage, process, refers to research into processes involved in the design and construction of buildings, and thus might include for example issues of representation, theories of design, modeling of the environment, and so on. The second, product, refers to research into buildings as projected or completed objects and systems and might include for example issues of aesthetics, materials, constructional techniques and so on. The third stage, performance, refers to research into buildings once completed and might for example include issues of social occupation, environmental performance, cultural assimilation, and so on. The advantage of this model is that it avoids the science/art and qualitative/quantitative splits, and allows interdisciplinary research into any of three stages. The model thus breaks the hold of research method and allows instead thematic approaches to emerge. It is possible for scientist and historian, academic and practitioner, to contribute to the research into each of the three stages. Most importantly the model also describes architecture temporally (as opposed to a set of static fragments), with one stage leading to another and, crucially, creating an iterative loop in which one stage is informed by another. For research to be most effective, and thus for architectural knowledge to develop, it has to feed this loop. For example:

A dynamic system thus emerges from this tripartite model, but it will only operate if academia and practice collaborate in order that the loop is continually fed with both data and analysis. However, this will open happen once we have cleared the three myths out of the way, and accept that architecture can, and should, be a research discipline in its own right, which both accords to the accepted criteria of research, but at the same time applies them in a manner appropriate to the issues at hand. There is some urgency in this, because as long as architecture fiddles around at the margins of the research debate, it will be confined to the margins of the development of knowledge. The present state of architecture, increasingly used to provide a velvet glove of aesthetics for the iron fist of the instrumental production of the capitalist built environment, is perhaps indicative that the state of marginality has been reached. The establishment of the discipline founded on research-led knowledge in the manner outlined above may be one small way of claiming a bit more of the center ground. Jeremy Till is Head of Central Saint Martin and Pro Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Arts London. Notes: A version of this paper was first written as a position paper for the RIBA Research Committee, and subsequently published on the RIBA Research Wiki. This is the reason that it starts with the RIBA Charter.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Municipal Gym of Salamanca / Carreño Sartori Arquitectos Posted: 03 Jan 2017 01:00 AM PST  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal

© Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal This sport facility located in Salamanca, was designed on 2007, but completed on 2016 due to the economic situation of the construction company. The 9-year period allowed specific modifications based on observations and opportunities given by the site. The initial ideas kept playing important roles and they finally modified the building.  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal A Place of Private Ground  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal  Section + Floor Plan Section + Floor Plan  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal The site, with an old gym, was next to a soccer field and an abandoned pool. All these sites were used as independent and private properties with blind enclosures, fragmenting the ground and unabling the possibility of continuity. All constructions were detached from the site boundaries, creating small and abandoned spaces.  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal A Project of Public Ground  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal The south façade faces the city, containing the main access of eventual use. The north façade, which receives direct sunlight, incorporate accesses and daily uses (gym/ machines, coffee and administrative offices). The east façade includes an access ramp that joins the pedestrian walkway, creating a direct path to the north tribune. The west façade includes emergency exits and complementary uses to the soccer field (reporter’s room and shared dressing rooms). The ground proposal is open to the pedestrian walkways, incorporating the original sites to the public paths and uses.  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal Public Sky  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal Most of the studied cases were characterized by the structural logic being over the space clarity.  Elevations Elevations With the main access in the south and without a previous space facing the building, the diagonal plane under the tribune increases its value.  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal Controlled Interior Light / Plane Misalignment  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal  Section Section  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal The series of planes are located in relation to the sun trajectory and the complementary uses. The lifted body has a faceted geometry related to the horizontal and diagonal ground-planes in which the building is inserted.  © Marcos Mendizabal © Marcos Mendizabal Structure and Force Transference  Courtesy of Carreño Sartori Arquitectos Courtesy of Carreño Sartori Arquitectos This force displacement deceives the eye, exposing a sort of floating pieces and constructive planes. With this structural strategy, two intentions are achieved: the clearance of the public ground and the interior controlled light.] This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Venice Isn't Sinking, It's Flooding – And It Needs to Learn How to Swim Posted: 02 Jan 2017 10:00 PM PST  Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco (2016). Image © James Taylor-Foster Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco (2016). Image © James Taylor-Foster "Will you look at that? St. Mark's Square is flooded!" An Australian day tripper is astonished. "This place is actually sinking," her friend casually exclaims. They, like so many I've overhead on the vaporetti, are convinced that the Venetian islands exist on a precipice between the fragility of their current (mostly dry) condition and nothing short of imminent submersion. With catastrophe always around the corner a short break in Venice is more of an extreme adventure trip than an elegant European city-break. If it were true, that is. Venice is not sinking – it's flooding. Since time immemorial the city has periodically flooded as a result of tidal patterns and residents are well-accustomed to its wintertime rhythm (and, less frequently, during the summer season). While acqua alta (high water) is a fascination for intermittent visitors it is little more than an accepted inconvenience for those who live with it: ground floor doors have to be sealed with barriers, boots and dungarees have to be fished out of the cupboard and, if the water is very high, boats might be unable to pass under the smaller of the city's hundreds of bridges until the water eventually subsides. Walkways are erected throughout the city's lowest areas (Piazza San Marco is, incidentally, particularly low terrain) and people continue to see to their daily business – only in a more elevated fashion. I once joined friends for dinner during a freak summer sirocco wind-induced acqua alta on the Fondamenta Ormesini – we sat outside, legs submerged, thinking little of the otherwise extreme conditions that the evening had proffered. Venice has always had an unusually intimate connection to the water which surrounds it. Its first settlers were refugees, fleeing to the marshlands where the city now stands in order to escape the genocidal tendencies of Germanic tribes and the Huns. The first structures they erected on the Rivoalto (a small constellation of high islands where the Rialto and its Palladian bridge is now positioned) were built atop wooden piles – a unique process of petrifying sunken columns in the silt of the swamp that is still in use today. Even as the city expanded into La Serenissima—the serene Venetian Republic, one of the most powerful thalassocracies that the world has ever seen—it was consistently reminded of its delicate, defensive and highly lucrative relationship with the lagoon and the Adriatic beyond. The ancient and mystical annual Marriage of the Sea, established in AD 1000, saw the Doge (the elected ruler of the Republic) hurl a consecrated ring into the murky waters and declare the city and sea to be indissolubly one. This liturgy, one can surmise, was a way of throwing caution to the wind and praying that prosperity would continue amid comparatively ungovernable natural conditions. _002_(1).jpg?1483398331) Canaletto's 'Il ritorno del Bucintoro nel Molo il giorno dell'Ascensione' (1730) Public Domain Canaletto's 'Il ritorno del Bucintoro nel Molo il giorno dell'Ascensione' (1730) Public Domain Astonishingly, this nuptial ceremony to the ocean also continues to this day – albeit in a different climate. Over recent centuries, and especially since the 1970s, Venice's economy has become almost entirely reliant on tourism; its unsurpassed naval might has been superseded by clumsy and unsettlingly large cruise liners and large swatches of San Marco, Cannaregio, and the Dorsoduro are now hotels, hostels and holiday houses. Many Venetians have either been driven about by lack of employment or have left of their own accord. Contessa Jane da Mosto, an environmental scientist who has lived in the city since 1995, is one who has actively made the lagoon her home. She married a Venetian—Conte Francesco da Mosto, himself an architect and author—and have together raised four children in the city against the background of a domestic exodus. When asked about the history of Venice and the water, Da Mosto points to a particular contemporary event that changed the future of the city: the flood of November 4th, 1966. Reaching 194cm (6'4), this was wholly unprecedented in the history of acqua alte. Heavy rain, a severe sirocco wind, crumbling infrastructure and entirely unready population isolated the city for twenty-four hours without repent. The flood revealed for the first time to what extent the built fabric of Venice had deteriorated – in the words of British art historian John Pope-Hennessy, "the havoc wrought by generations of neglect." "Venice lives thanks to big disasters such as this," Da Mosto argues. "They have caused [the city] to fundamentally change direction." At the point in time in which the 1966 flood occurred more and more of the lagoon was being absorbed by the expansion of the Marghera industrial zone. "The national and international attention that followed this event changed the emphasis to safeguarding the heritage of the city." As part of what became known as the International Safeguarding Campaign, investment flowed into Venice from around the world and its decaying skeleton began to breathe new life.  Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco in 2015. Image Courtesy of MOSE Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco in 2015. Image Courtesy of MOSE In November last year, fifty years on from the flood, We Are Here Venice—an organisation founded by Da Mosto to raise awareness of the problems that the city faces in the 21st Century—inscribed a simple blue line around shop windows and doorways of Piazza San Marco. L'Acqua e la Piazza (The Water and the Square) graphically indicates just how high the water rose that day. "A strong storm surge meant that the water didn't leave the lagoon when the tide turned and, combined with a sort of oscillation in the Upper Adriatic (just like when you're in the bath and the water rocks back and forth), extra water was pushed into the lagoon." As the water was expelled and 'hit' the opposite coastline of the Adriatic, it simply returned and washed back into Venice a few hours later. This back and forth motion, Da Mosto explains, can occur for days on end until the water eventually dissipates down into the Mediterranean Sea. Following the disaster, which also caused considerable damage in other Italian cities, repairs and restorations were carried out to ageing monuments. In the 1980s, MOSE (named in an homage to Moses, the Biblical figure who was said to have parted the Red Sea) was commissioned: four vast retractable gates at the inlets of the Lido, Malamocco and Chioggia which, when operational later this year, will be able to seal the entire lagoon from high tides in fifteen minutes flat. The project, akin to the Thames Barrier in London or the Maeslant Barrier in Holland, has been mired in a corruption scandal (€5,493,000,000 has been spent on the project to date) and is by no means a perfect solution. "Even when the mobile barriers start operating," Da Mosto iterates, "Piazza San Marco will still be flooded many times a year. […] It's absurd to think that mobile barriers alone can save Venice. They are just one of the many measures that are needed in the lagoon."  Lido Inlet of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE Lido Inlet of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE  Chioggia Inlet of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE Chioggia Inlet of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE  Malamocco Inlet of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE Malamocco Inlet of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE "The last thirty years," she explains, "have been heavily conditioned by strong lobbies that permeated every crack and corner of the cultural, scientific and economic life of Venice. They have all been associated with this huge flow of investment through the 1973 Special Law for Venice 1973 [which aims to "guarantee the protection of the landscape, historical, archaeological and artistic heritage of the city of Venice and its lagoon by ensuring its socio-economic livelihood"] that was directed at building the mobile barriers. But, as the scandal has revealed, over one billion Euros can not be traced. On top of that, the money spent on the actual works has been shown to have been spent at inflated prices. So not only did a huge amount of money disappear, but they simply spent more than they should have."  Construction of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE Construction of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE  Construction of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE Construction of the MOSE Project. Image Courtesy of MOSE For a city which has always heavily relied on an economy driven by foreign trade or investment, plans on the scale of the MOSE project are nothing new. Venice has always made courageous decisions to maintain accessibility between the sea and the city. "When the lagoon first started to silt and navigation became difficult, the city diverted whole rivers further south or further north of the lagoon so that less sediment came in so they could keep the channels deep for the galleons," Da Mosto clarifies. "Subsequently, during Austrian occupation at the end of the 19th Century, the entire coastline of the barrier islands to Venice were reinforced and proper inlets were built to ensure that access to the lagoon was deep and wide." Unfortunately, as a consequence of that and many other similar moves, Venice is at risk of no longer being part of a lagoon system at all; as channels are dredged ever deeper to accommodate the likes of MS Queen Victoria (a 90,049 gross ton pleasure-cruiser operated by Cunard) in port, it is being transformed into less of a lagoon and more into a bay of the sea – and that, according to Da Mosto, "has very important implications for the integrity of the city as well as its biodiversity and ecological functions [see 'Criterion (v)' at the foot of this article]." There can be no doubt that Venice lives thanks to the regular exchange between the lagoon and the sea and, while there is still inherent resilience in the system, much has been neglected over the preceding decades. "We're beyond the times when some ministry for infrastructure and public works can just come and do what they want to do, or what business interests make them do," Da Mosto argues. "The whole city needs to wake up." Find out more about the activities of We Are Here Venice, here.  Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco. Image Courtesy of We Are Here Venice. Image © Anna Zemella Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco. Image Courtesy of We Are Here Venice. Image © Anna Zemella Venice's Inscription as a World Heritage Site (1987)Venice and its lagoon were inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1987. According to the citation, they "form an inseparable whole of which the city of Venice is the pulsating historic heart and a unique artistic achievement. The influence of Venice on the development of architecture and monumental arts has been considerable." The inscription was based on the following six criteria (you can read the full document in multiple languages, here):

Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco. Image Courtesy of We Are Here Venice. Image © Anna Zemella Acqua Alta in Piazza San Marco. Image Courtesy of We Are Here Venice. Image © Anna Zemella This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| BigBek Office / SNKH Architectural Studio Posted: 02 Jan 2017 09:00 PM PST  © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan

© Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan From the architect. The office of Armenian software development company BigBek is located in Yerevan's Soviet era automotive manufacturing plant called ErAZ (Erevanskiy Avtomobilny Zavod) which is now transforming into office spaces for Armenia's intensively growing IT community.

The main goal of this project was to create an open workspace for up to 30 employees with a strict functional division in only 177 square meters. Besides the main workspace, the client asked for a lounge zone, a small kitchen and a meeting room. To keep the space as open as possible we made a decision to divide the functional zones without physical barriers, by creating optical ones. Each zone has its own color which makes visible borders between them. The location of each listed above zone was dictated by the shape of the floor plan.  © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan The bright colors, geometry and brutal concrete ceiling of this interior are creating a dynamic, playful and creative atmosphere for work. The first decision we made during the design process was to keep the old Soviet era prefabricated concrete slabs exposed, to highlight the industrial charisma of the building. The kitchen is envisioned like a projection of a yellow box into the corner of the space. Its bright, saturated yellow outline creates an invisible volume in the space which interacts with the magenta colored meeting room, the only physical volume in the interior.  © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan We've tried to make the main lighting design as minimal as possible using cross-like organized 1.5m long LED tubes which are graphically interacting with the intersecting colors of the wall in the back of the office.  © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan Product Description. Armstrong's linoleum flooring had a big impact on the final result of the project as it gave us freedom to implement our primary ideas in this interior. We found all the needed colors for the division of different zones of the interior as we envisioned it. The technical characteristics of the material and its durability are satisfying for commercial use.  © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan © Sona Manukyan & Ani Avagyan This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| You are subscribed to email updates from ArchDaily. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

.jpg?1483435068)

.jpg?1483435792)

.jpg?1483435428)

.jpg?1483435243)

![Casa de la Lluvia[de ideas]: cultural community space. Break dance workshop. Bogotá, 2013.. Image © Arquitectura Expandida. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize Casa de la Lluvia[de ideas]: cultural community space. Break dance workshop. Bogotá, 2013.. Image © Arquitectura Expandida. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize](http://images.adsttc.com/media/images/586b/d028/e58e/ceb3/af00/000c/thumb_jpg/casa_de_la_lluvia-breakdance.jpg?1483460630)

![Trincheras [Trenches], Malaga 2015. Self-building process of 2 self-funded classrooms for students. Image © Recetas Urbanas. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize Trincheras [Trenches], Malaga 2015. Self-building process of 2 self-funded classrooms for students. Image © Recetas Urbanas. Courtesy of Curry Stone Design Prize](http://images.adsttc.com/media/images/586b/d4d3/e58e/ceb3/af00/0012/thumb_jpg/Trincheras__Ma%CC%81laga_2005_credit_Recetas_Urbanas.jpg?1483461821)

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar